A statue of M.Q. Sharpe, the only South Dakota Governor from Lyman County, was unveiled in the Capitol Rotunda at Pierre on Friday, June 15, 2018. The life-size bronze statue of Gov. M. Q. Sharpe by sculptors Lee Leuning and Sherri Treeby of Aberdeen pays tribute to Sharpe’s role in developing the Missouri River dams and portrays Sharpe in fishing gear, holding a northern pike. It is slated to be placed near Lake Sharpe, named for him, in front of the American Legion Post 8 “cabin” at the end of Pierre Street on Island View Drive.

Lee Leuning notes that, “although Sharpe was known as a 'lawyer's lawyer,' a public servant, and an independent politician, this portrayal of Gov. Sharpe was selected to recognize the lasting impact the development of the Missouri River has brought to South Dakota’s economy.” Leuning continued, “In actuality, he may have done more overall for South Dakota than any other Governor!”

Merrill Q. Sharpe was South Dakota’s 17th Governor, who served our state from 1943-47, is best-known for his tireless pursuit of building the Missouri river dams. During Gov. Sharpe’s term of 1943-45, A.C. Miller of Kennebec, who practiced law across the street from Sharpe, served as Lt. Governor. Lyman County is the only county to have two residents in the state's top two offices.

A Kansas native, Sharpe worked as a news reporter, and surveyor. He served in the U.S. Navy prior to World War I. After leaving the Navy, he moved to South Dakota and graduated from the USD School of Law in 1914. He opened successful law offices in Oacoma and Kennebec and later served as Lyman County’s States Attorney. Elected State Attorney General in 1928, Sharpe earned statewide recognition through his investigative efforts into the State Banking Department, from which the State Banking Superintendent. had embezzled over a million dollars. In a second investigation, Sharpe uncovered “mishandled funds” in the failing Rural Credits Program which had occurred during the Norbeck and McMaster administrations.

After losing his re-election bid in the FDR landslide of 1932, Sharpe returned to his Lyman County law practice until 1937, when he was named Chairman of the SD Supreme Court Codification Commission by Gov. Harlan Bushfield. The Commission's task was to codify all of South Dakota’s laws and finish in 1939. Sharpe also accepted an appointment to the Missouri River Development Committee, becoming its chairman when elected Governor.

During the war years, Gov. Sharpe led the state Civil Defense and rationing effort and formed a State Veterans Department. After the war, Sharpe initiated a state building and development plan, created the State Police Radio network, founded the State Park system, re-energized the teacher’s pension fund and, most importantly, supported the repeal of a state income tax. He served as an attorney for the South Dakota Sioux Tribes and was instrumental in the development of rural electrification. In 1959, Sharpe served as chairman of the Citizen’s Tax Committee during Gov. Herseth’s administration.

Gov. Sharpe married Emily Auld of Plankinton in 1918, and they had one daughter, Lorna. Mr. Sharpe passed away on January 22, 1962 and is buried at the Oacoma cemetery.

Things you may not know about Gov. Sharpe:

He was diminutive in size but, was known to be tough, tenacious and thorough in his actions.

He won the 1942 Republican nomination for Governor after no individual received a majority in a four-way race.

He declined the building of a partisan “party machine” and made appointments based on ability.

He refused to buy a tuxedo for his inauguration as “it would be 'improper' during these troubling war times.”

As Governor, he refused his salary, instead, using the money to buy war bonds.

He owned land eight miles west of Oacoma, upon which Lyman County’s first mining operation was established.

Lyman County includes the towns of Oacoma, Kennebec, Reliance, and Vivian, and portions of the Lower Brule Reservation.

South Dakota's WWII Era Manganese Mine

Landmarks: What are Those Mysterious Ruins off the I-90 West of Oacoma?

(Repost of SDPB blog from October, 2018. Text and photos by Michael Zimny.)

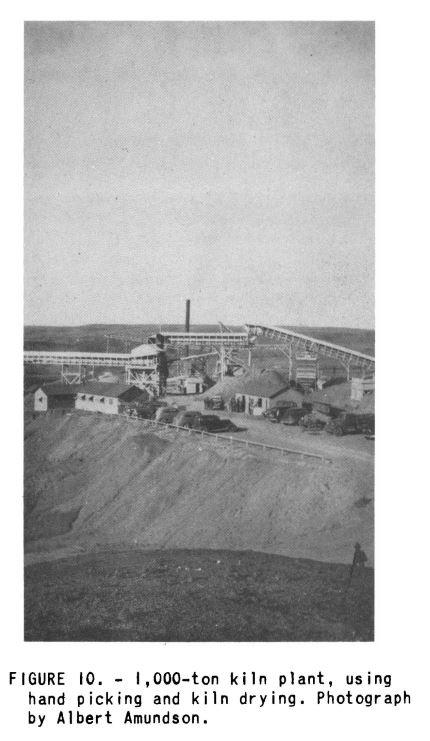

Frequent cross-state travelers may sometimes wonder: What the heck are those brick and concrete just north of the of I-90 a few miles west of the river? All alone on the swollen grass seas west of Oacoma, their mystique recalls Caspar Friedrich's depictions of pastoral ruins.

So what are they?

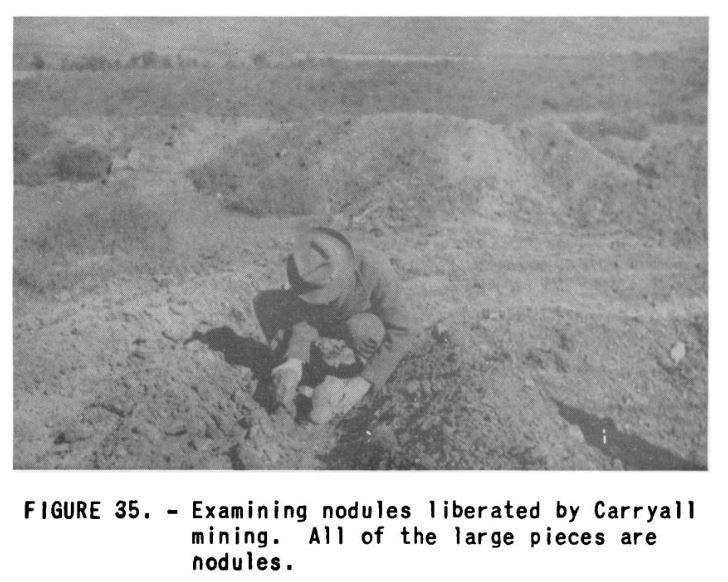

The vestiges of what was a sizable manganese mining operation. According to a local, the open-ended concrete structure was a mine shaft and the brick building housed an auger.

Manganese — which is instrumental in steel production — was discovered in the black soil strata of the river bluffs in the 1920s. In 1929, the Deadwood Pioneer Times announced the formation of the General Manganese Corporation, dedicated to mining the metal from what it described as "undoubtedly the largest deposit in America."

State attorney general and future governor Merrill Sharpe, who farmed and practiced law in Oacoma was involved in the project from the outset, acquiring much of the land.

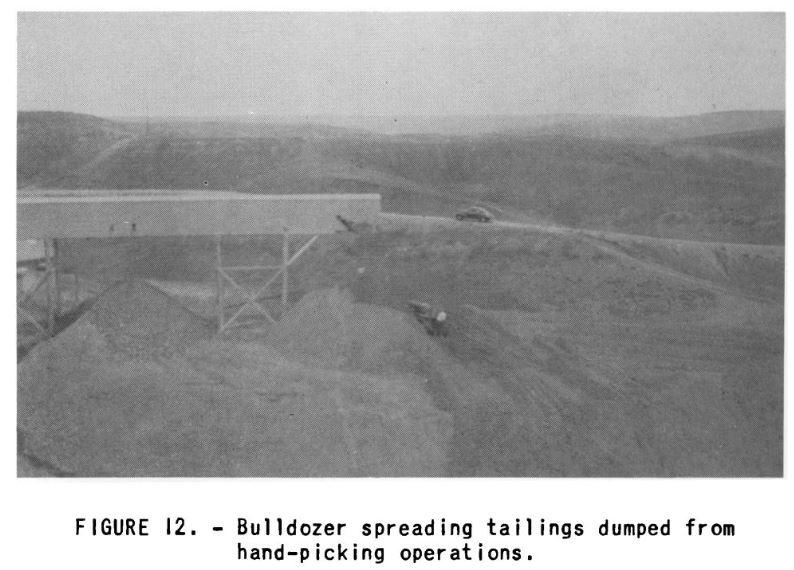

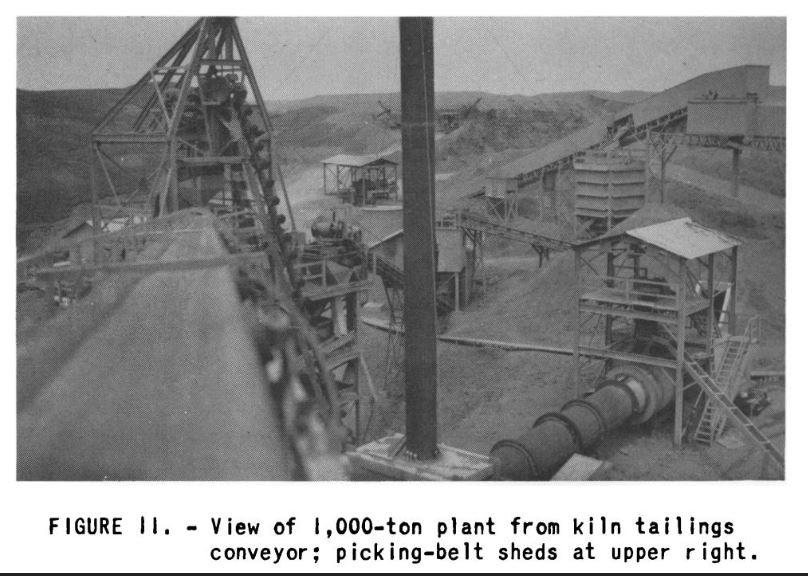

The operation picked up steam as the build up to US entry into World War II called for more steel, and consequently more domestic manganese production. Prior to the war, America was dependent on Russian imports. In 1941, the Argus Leader claimed that, "Up to 95 percent of our steel needs... have come from Russia, where it was mined practically with slave labor producing a very economical ore." Most likely, the short-lived Molotov-Ribbentrop pact between Nazi Germany and Russia impressed upon US planners the need for manganese-independence.

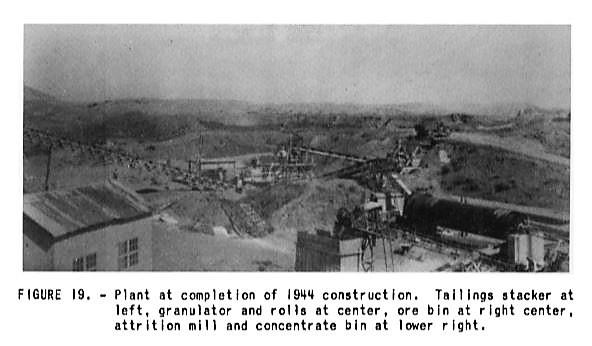

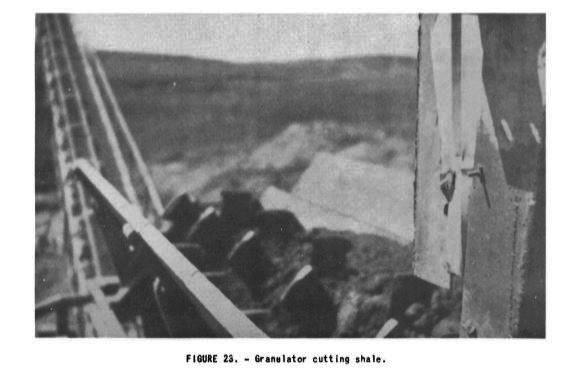

In 1941, the increased demand led the federal government to build a pilot plant to experiment with cost-effective methods for separating manganese from the surrounding shale. After the war, local papers reported that Merrell Sharpe, who had leased the land to the government, announced plans to utilize processes developed by the Bureau of Mines to expand private mining operations. Those methods must not have proven cost-effective enough to compete with imports in the post-war economy. A 1954 Rapid City Journal article on the flooding (for Lake Oahe) of Oacoma gave it a "last chance for survival as an important town if supplies of manganese are cut off from Brazil and Russia."

To date, the Oacoma manganese deposits are still considered too low-grade to compete with those in say, South Africa. One day a new technology may unleash their potential. Then condominiums will kiss the skies on either side of the Oacoma/Chamberlain divide, straddled by a space-age bridge designed by Santiago Calatrava. For now, they're mouldering reminders of that time we tried to simultaneously stick it to the Third Reich and the damned Russkies.

Note: The old mining site is on private property. The photographer was granted permission to access. Please enjoy respectfully from the road.