On the Edge of Space: The Explorer Expeditions of 1934-1935

Gene Bauer

South Dakota History, volume 12 number 1 (1982)

South Dakota History is the quarterly journal published by the South Dakota State Historical Society. Membership in the South Dakota State Historical Society includes a subscription to the journal. Members support the Society's important mission of interpreting, preserving and transmitting the unique heritage of South Dakota. Learn more here: https://history.sd.gov/Membership.aspx. Download PDFs of articles from the first 43 years and obtain recent issues of South Dakota History at sdhspress.com/journal.

On a cold Armistice Day in 1935, two Army Air Corps pilots climbed into a metal ball fastened to a balloon of rubberized cotton and flew it to a height of 13.7 miles. Seven years later, information gained from that flight was being employed in the United States Air Force high-altitude planes that were giving American airmen superiority in the skies of Germany and Japan, By 1958, that information was bearing further fruit in the unmanned rockets of the United States space program, and scientists were starting to apply the research and methods to the manned flights that would succeed in the 1960s.' By 1970, man had escaped earth's atmosphere and landed on the moon, but the first step in America's movement into space, the highflying cotton balloon called Explorer II, had been launched on 11 November 1935 from a site only eleven miles south of Rapid City, South Dakota.

By balloon or rocket. United States scientists had been trying to reach and study the boundaries of space since the late 1920s Public awareness and financial support had lagged behind until the successes of a foreign nation spurred the country's interest. In the 1930s, general interest in atmospheric exploration increased after Auguste Piccard of Switzerland flew a free-flying balloon to a height of 51,775 feet (9.81 miles) on 27 May 1931. In August of 1932, Piccard, using the first sealed gondola, broke the ten-mile barrier with a flight to 53,153 feet. These flights proved that expeditions to altitudes of over eleven miles, or into the stratosphere, were possible.

Following the Piccard flights, the Army Air Corps and the National Geographic Society combined their resources and in 1933 began planning the United States Stratosphere Expedition. After design and construction of the craft were well underway, planners moved to select a launching site. A committee of Army Air Corps personnel was in charge of site location. This committee believed that three conditions were necessary in a site. It had to be far enough west to permit the balloon to drift about eight hundred miles eastward and still land in relatively level, unforested terrain. The area had to have good summer flying weather, and the site had to be sheltered from surface winds.

Early in 1934, the Rapid City Chamber of Commerce learned of the search for a location and invited the committee to consider Rapid City, a small town in western South Dakota on the edge of the Black Hills. When the Army Air Corps site committee arrived in Rapid City in March 1934, they were shown Halley Airport. Local tradition suggests that the committee was unhappy about being brought all the way to South Dakota to see an airport. With hundreds of airports in the United States to choose from, the committee explained, this was not what they were looking for. Luckily, Ben Rush, chairman of the Pennington County commissioners, had been giving the site requirements a great deal of thought and had located a "hole" in the ground about eleven miles south of town near the Bonanza Bar Mine. With the help of the nearby Civilian Conservation Corps camp at Rockerville, Rush had a trail cut through to the rim of the bowl. The Rapid City businessmen persuaded the location committee to stay and look at this site. As the head of the site committee looked down into the treeless, bowl-shaped depression, he exclaimed, "God made that spot for a stratosphere flight."

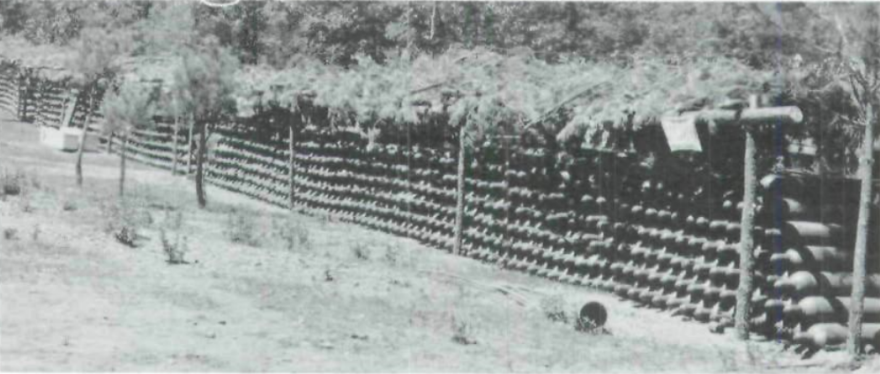

The committee chose the Stratobowl, as the Black Hills site became known, on condition that the Rapid City Chamber of Commerce make the arrangements for leasing the land and building a road to the rim of the site and down into the bowl that would be suitable for heavily loaded trucks. The business parts of the project, the offices, storage sheds, workrooms, and a weather office, also had to be arranged locally. Rapid City residents quickly raised ten thousand dollars toward the project and set to work to have the bowl ready by July 1934. By the end of 1935, hundreds of South Dakotans had worked on the project and more than nineteen thousand dollars had been raised within the state.

For the first attempt at the United States stratosphere flight, the Army Air Corps brought in a crew consisting of Major William E. Kepner, flight commander; Captain Albert W. Stevens, scientific observer; and Captain Orvil A. Anderson, pilot. Communications were rapidly set up. The balloon bag, weighing two and a half tons, was brought in by truck. Cylinders of hydrogen were shipped by rail, and airplane loads of instruments were flown into Rapid City. On 9 July 1934, the last of the preparations were complete, and the expedition awaited favorable weather conditions. Finally on 27 July 1934, the necessary high pressure area drifted in, and inflation of the balloon began. The next day at 5:45 in the morning. Explorer I (this name would be used again for America's first artificial satellite) was launched.

Inside the gondola, the crew members took air samples and worked with sensitive scientific instruments as the balloon rose to a height of 60,613 feet (11.5 miles). At that point, the balloon developed a split across the bottom, and the craft began to drop rapidly. At about five thousand feet, the balloon exploded. The heavy gondola plummeted to earth, but the three men succeeded in leaving it and parachuted safely to the ground. The Explorer I crashed in a cornfield near Holdrege, Nebraska, where the nine-foot gondola was reduced to a two-foot pile of debris.

Although the flight itself was a failure, some of the photographic records of the trip survived the crash, and some of the scientific instruments released by parachute also survived. Furthermore, the gondola had performed well, protecting the crew from the thin air and intense cold of the stratosphere. Explorer I had shown that man should be able to live and work at heights inimical to human life. Expedition planners were not discouraged. Most importantly, the sponsors of the expedition had heavily insured Explorer I, and the recovery from the insurance made it possible to fund further expeditions. Accordingly, the National Geographic Society and the Army Air Corps planned expeditions for 1935.

The 1935 expeditions were to be held in July and August. The first balloon, an improved design, would again use hydrogen gas; the second would use helium. During the night of 11 July, the new Explorer was inflated in the Stratobowl and stood ready for flight in the early morning of the twelfth. Before the gondola could be attached, however, the balloon unexpectedly exploded, ending the July expedition abruptly. The fault lay in the balloon's rip panel, which was too large. The sponsors and personnel of the flight were as close as they ever came to abandoning the project. Studying the collapsed balloon, the designers, Goodyear-Zepplin employees, were able to correct the flaw in design, however, and expedition sponsors decided to go ahead with the second 1935 flight. Lack of favorable weather conditions around the Stratobowl during the rest of the summer of 1935 delayed the second flight until temperatures had dropped considerably. Meteorologists for the expedition had to ensure the absence of wind in the Stratobowl on the night of inflation, a cloudless day for the flight, and a ground wind of not more than fifteen miles per hour in the landing area. Such a prediction would be no easy task even now, but the meteorologists for Explorer II finally picked an almost perfect day for the flight. It was cold, but the important consideration was that no wind was blowing. Under lights set up by the Homestake Mining Company, the second 1935 balloon was inflated and rigged for flight during the night of 10 November 1935.

The balloon, made of two and two-thirds acres of a new rubberized cotton, was filled with helium gas. Again, a problem developed during inflation. The balloon had been stored at a temperature of fifty degrees Fahrenheit, but as it was spread out for inflation, it quickly cooled to near zero degrees. It became difficult to stretch, and coils of fabric in the pile under the rising balloon became cramped. As the balloon grew in size, a large pocket of gas formed in the cramped pile and was submitted to the full pressure of the helium coming through a ten-inch canvas hose, causing a tear. A full hour was spent searching for the rip, which, when found, was seventeen feet long. Planners called a hasty conference to determine whether or not a launch was still possible. Goodyear-Zepplin technicians decided that the huge rip could be repaired. A two-inch strip of tape and then a five-inch patch were cemented along the tear, and the inflation proceeded without further incident.

Standing ready to be attached to this massive balloon was a gondola nine feet in diameter, which was made of a new magnesium alloy that had yet to be thoroughly night-tested. The alloy, called Dowmetal, was obtained from brine that had been pumped to the surface from hundreds of feet below the earth. It was lightweight and sturdy. The gondola was painted black on the bottom to absorb heat from the earth and white on the top to reflect sunlight. To conserve weight. Explorer II would carry only two human passengers. Captain Albert Stevens was flight commander and scientific observer. Captain Orvil Anderson would pilot the craft. Captain Randolph P. Williams was in charge of ground operations and would serve as an alternate pilot if the need arose.

On 11 November 1935, at 7:01 a.m., mountain standard time, thirty-five to forty thousand people watched as Explorer II, weighing seven and one-half tons, lifted from the Stratobowl. About two hundred feet above the ground, a seven-mile-per-hour gust of wind suddenly blew the balloon down and toward the cliffs on the east side of the stratosphere bowl. The crew immediately dumped 750 pounds of ballast (very small lead shot), much of which fell on the heads of the spectators who were crowding the rim of the bowl. By using an electric ballast discharge, the crew was able to drop the ballast in three seconds. Following the discharge of lead shot, the Explorer II took off with great speed, clearing the rim easily.

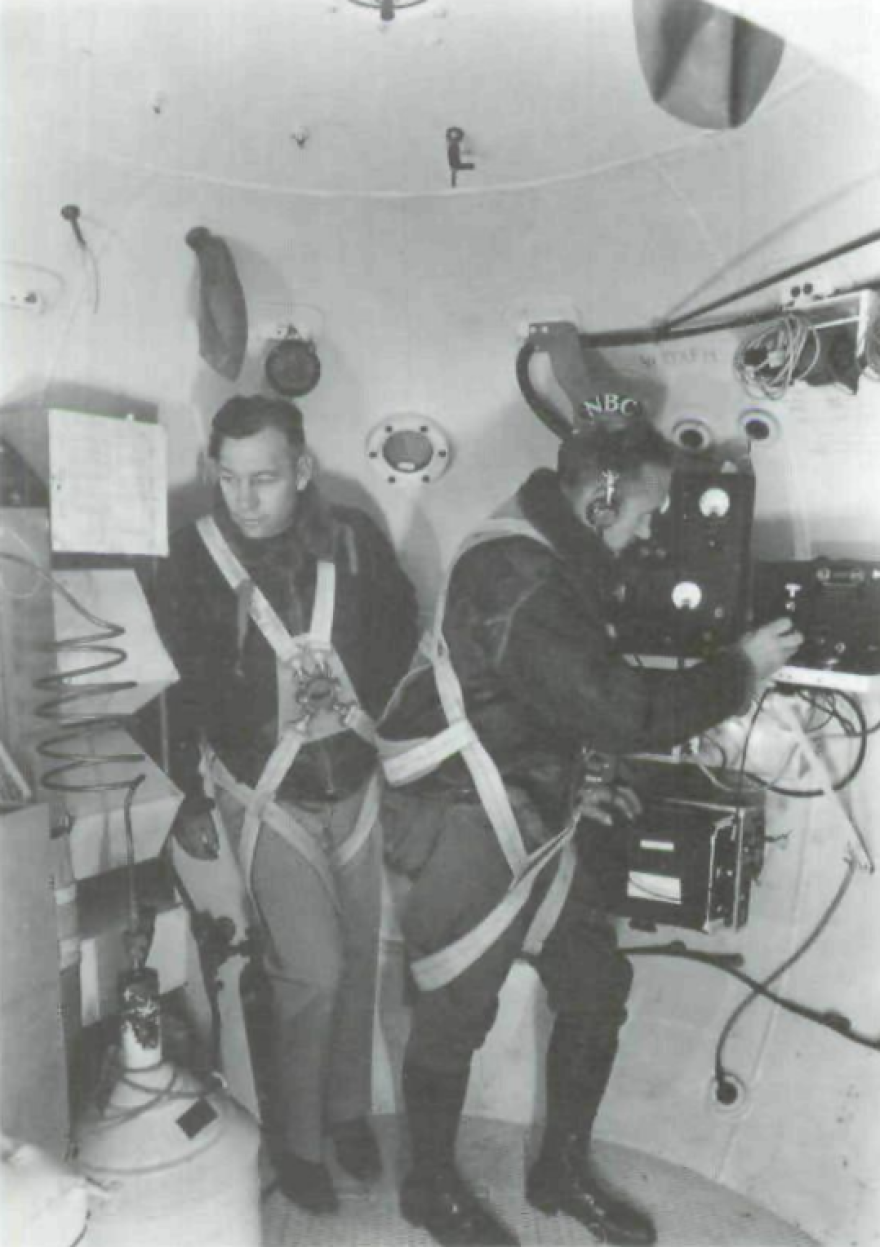

At 16,000 feet, Stevens and Anderson climbed out of the gondola to inspect the rigging. The ten one-inch ropes that suspended the gondola from the balloon were stretched taut and formed a rigid cage on top of the gondola in which the two men could work safely. At 17,000 feet, the men reentered the gondola, sealing the manhole behind them. The air inside the craft was then pressurized to a density equal to an altitude of 13,000 feet. This pressurization enabled the crew to work in comfort for the duration of the flight. The temperature inside the gondola fell to a frosty twenty one degrees Fahrenheit, but then rose to a comfortable forty three degrees as the craft reached an altitude of thirteen miles. Outside the gondola, air temperatures varied from seventy to seventy-eight degrees below zero.

At 11:40 a.m., mountain standard time. Explorer II reached the top of its flight. The men in the gondola were 13.71 miles, or 72,395 feet, above sea level. They had been above 70,000 feet since 10:30 a,m, and would spend a total of one hour and forty minutes at these record-breaking altitudes. When the top figure of 13,71 miles had been announced to reporters, the crew, who had excellent radio hookups, overheard one reporter's suggestion regarding early publicity, "Don't play up this record business, boys, until we are sure that they have gotten down safely," the reporter radioed to his affiliates. "There is still plenty of chance for them to crash and they have to come down alive to make it a record.

Stevens and Anderson could have taken their balloon higher if the gondola had not been so heavy and they had not expended so much ballast in the take-off, but over a ton of scientific equipment was sharing the gondola with them. More than an altitude record was at stake. At 13.71 miles, 96 percent of the air in the atmosphere was below the balloon. Consequently, Explorer II was able to make an almost complete study of the atmosphere and of cosmic rays, which was the primary purpose of the expedition. The balloon carried sixty-four different scientific instruments, and these instruments provided new information on the direction, number, and energy of cosmic rays, on the distribution of ozone in the upper atmosphere, on the brightness of sun and sky, on the chemical composition, electrical conductivity, and living spore content of the air above 70,000 feet, and on radio transmission at high altitude,'' The scientific benefits of the flight would not be equaled until the flight of Apollo 8, but, as Hugh L. Dryden, director of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics in 1955, pointed out, perhaps the most significant accomplishment of the Explorer II was its "convincing demonstration that man could protect himself from the environment of the stratosphere." The advanced pressurized cabin, the magnesium alloy of the gondola, the men's equipment, such as electrically heated flying suits and the two-way radio hookup, were now flight-tested and during world War II would be improved and used in the designs of fighter planes. The experience gained and the scientific data base of the Explorer II would ultimately lead to the successes of the United States space program, but all of that was still in the future at 11:40 a.m. on 11 November 1935.

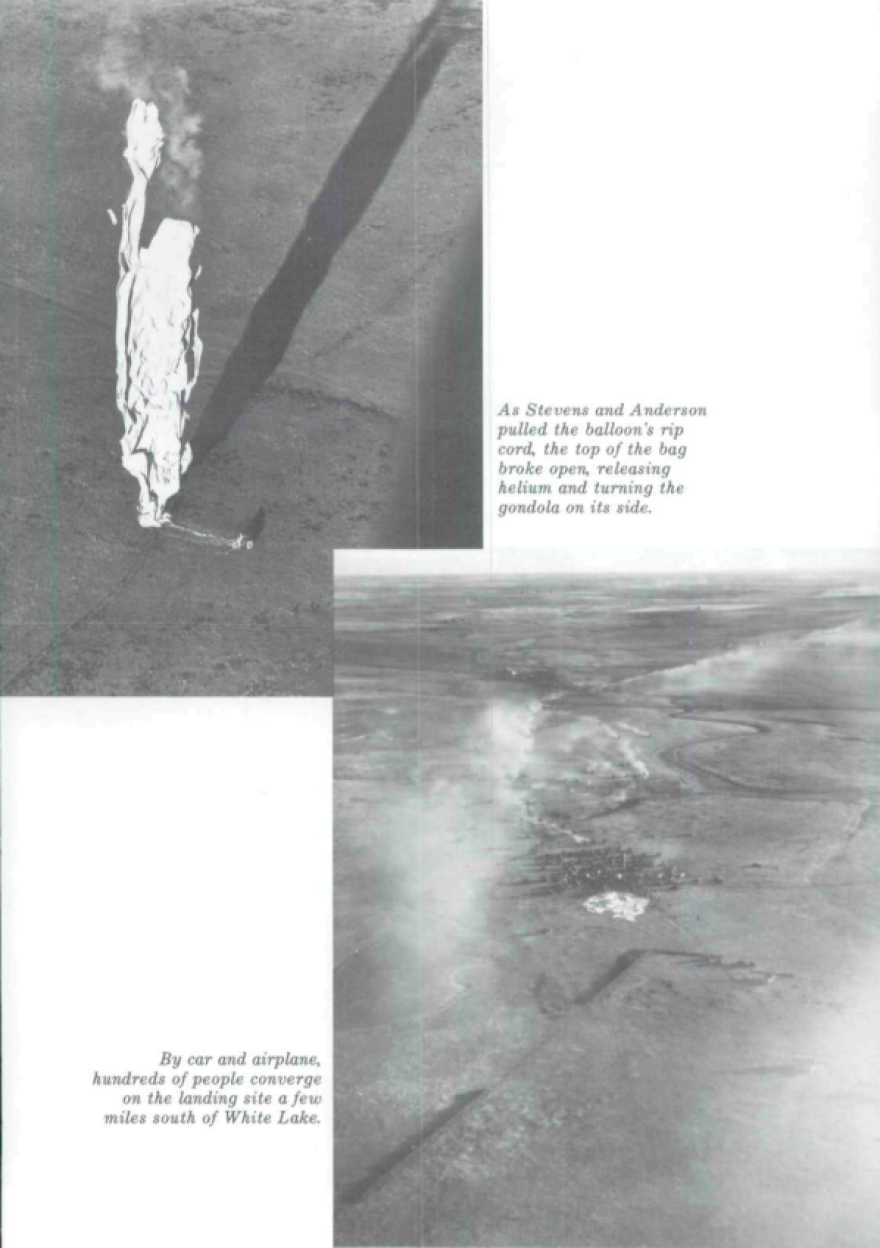

Stevens and Anderson had more than thirteen miles to go before they would set the world altitude record and safely land their scientific experiments. At about noon. Captain Anderson released helium from the balloon to start the descent. The descent was gradual until the craft reached 40,000 feet, where the air density increased and the balloon began to drop at 600 feet per minute. The balloon had drifted 230 miles east across South Dakota during the flight, and Anderson looked for a likely field in which to land the craft. Captain Stevens graphically described the touchdown: "We donned the football helmets loaned us by the Rapid City School, stretched a safety belt across the gondola, and then as the gondola nearly touched the ground, we pulled together on the ripcord. The top of the bag instantly opened. It deflated so quickly that the gondola turned over on its side. Hanging to the safety rope we swung to the center of the car, while objects of all descriptions, that had been on the floor, hurtled by us. We groped around with our feet and found that we were standing on some of our instruments."

In spite of the last minute discomforts, the landing was "eggshell" perfect about twelve miles south of White Lake, South Dakota. Stevens and Anderson were unhurt but were startled when eager spectators peered into the porthole of the gondola before they could climb out. As the "stratonauts" left their craft. thousands of people who had been tracking the balloon from the ground converged on the site. Fifty men from the Civilian Conservation Corps camp at Lake Andes were soon on hand to control the crowd. Minutes later, they were joined by a unit of the Fourth Cavalry from Fort Meade. Meteorologists had dispatched this Fort Meade unit from the Stratobowl in the morning. Traveling over poor roads, the cavalry had arrived at the landing site moments after touchdown. The crowd was easily handled, and no damage was done to the craft or equipment. The Explorer II had been aloft for over eight and a half hours and had set a world altitude record. In his reports of the flight. Captain Stevens expressed the hope that more stratosphere flights would be planned, but he realistically admitted that they were expensive and risky. In addition, the scientific information from the 1935 flight had yet to be studied and analyzed, and not much more could be gained by staging another expedition immediately." Not until 8 November 1956, when two United States Navy pilots again left the Stratobowl and rode a giant sky-hook balloon made of plastic to a height of 76,000 feet (14.4 miles), would tbe 1935 altitude record for balloons be broken. By 1956, however. United States Air Force planes, using information gained from Explorer II, had already attained altitudes of 90,000 feet, making altitude records for balloons less spectacular. Still, only the balloons had the capacity to remain at heights of fourteen or fifteen miles long enough to study the effects of the high altitude. The purpose of the 1956 United States Navy expedition from the Stratobowl had been to study the medical effects of high altitude on humans." The age of manned space flights was just around the corner, but scientists were still using balloons to gain information about the conditions astronauts would encounter.

In 1957 Sputnik I and in 1958 Explorer I, the first United States unmanned satellite, thrust free of earth's gravity. Captain Albert W. Stevens, who had been questioned about the feasibility of such flights in 1935, had labeled them impossible. Although he did not know it at the time, it was his Explorer II, a cotton balloon and large metal ball, that had provided the data base and flight tested the equipment that would be refined until the United States not only broke free of the earth's atmosphere but succeeded in landing men on the moon.

South Dakota History is the quarterly journal published by the South Dakota State Historical Society. Membership in the South Dakota State Historical Society includes a subscription to the journal. Members support the Society's important mission of interpreting, preserving and transmitting the unique heritage of South Dakota. Learn more here: https://history.sd.gov/Membership.aspx. Download PDFs of articles from the first 43 years and obtain recent issues of South Dakota History at sdhspress.com/journal.