The sound of the party filters across the mansion's lawn long before you see it: Dozens of guests spill out onto the front porch of the stately Fendall Hall in Eufaula, Alabama.

It's an engagement party, and past the people drinking white wine in the main hall is one of the home's historians, Susan Campbell.

She swings open the door to the expansive backyard.

"They had, like, 5 acres or so," Campbell says of the former owners, the Young-Dent family. They built the house in the late 1850s.

But you might already know this, because planted in the front yard of this historical home is a large, black-and-gold, square metal historical marker with the seal of the Alabama Historical Commission — and it says so.

Edward Brown Young was a "banker, merchant and entrepreneur," it says. He "organized the company which built the first bridge" in Eufaula, and his daughter married a Confederate captain in the "War Between the States."

What the marker doesn't mention, however, is that Young was a cotton broker, one of the most powerful men in the slave trade. Nor does it mention that he owned nine slaves, according to the federal 1860 census.

And while the sign claims the company he organized built the bridge, that bridge, spanning the Chattahoochee River, was actually designed, managed and built by a slave named Horace King, a renowned and gifted engineer, along with a large group of enslaved men.

Campbell says she'd like to see more of this information included.

"But that's because I'm a Northerner, not a Southerner," she says. She moved to the South 20 years ago from Michigan. She says most people she knows here wouldn't agree with her.

"I mean, they know," she says, glancing over at the revelers on the porch. "They know it. But [they] don't necessarily want to be reminded."

That's the difficult thing about the truth. It's just not as fun to throw parties in places where terrible things happened.

How the U.S. tells its own story is a debate raging in schools, statehouses and public squares nationwide. It has led to social movements and angry protests. But for more than a century, historical markers have largely escaped that kind of scrutiny.

With more than 180,000 of them scattered across the U.S., it's easy to see why:

Even governments don't really know what they all say. Many state officials told NPR that they have no idea what signs are in their state, what stories they tell or who owns them.

And while markers often look official, the reality is that anyone can put up a marker — more than 35,000 different groups, societies, organizations, towns, governments and individuals have. It costs a few thousand dollars to order one.

Over the past year, NPR analyzed a database crowdsourced by thousands of hobbyists, looking to uncover the patterns, errors and problems with the country's markers. The effort revealed a fractured and often confused telling of the American story, where offensive lies live with impunity, history is distorted and errors are sometimes as funny as they are strange.

Three separate states, for example, have markers that claim to be the place where anesthesia was discovered. Two states, Kentucky and Missouri, both claim to be the home of Daniel Boone's bones. Michigan and Alabama both claim to be the home of the first railroad west of the Allegheny Mountains, while Maryland and New Jersey both claim to have sent the first telegram.

Texas, on the other hand, claims to be the home of the first successful airplane flight — completed by a man who was neither of the Wright brothers.

Meanwhile, dead animals are rampant. Florida marks a dead alligator named Old Joe; California marks a dead horse — also named Old Joe. Arizona put up a marker for a donkey that drank beer. California thought it had a dead mastodon until a marker explained it was actually a dead circus elephant.

Somewhat dead humans are also popular. There are markers memorializing 14 ghosts, two witches, one vampire, a wizard and a couple who, a New Hampshire marker says, may have been abducted by aliens.

But the deeds of men are far more prevalent, even if questionable. Nevada marks a man who killed 11 people in the 1850s, even though it notes he had "few, if any redeeming traits." Arizona, on the other hand, marks the grave of a man the local town wrongly hanged for stealing a horse in 1882. It says, "He was right. We was wrong. ... Now he's gone."

There are markers to "world famous" items that few could likely pinpoint: soda water, cantaloupes, roofing slate, mustard, frozen custard, French-style cheese, beef jerky, a Santa Claus school, bourbon ball candy and dozens of others.

These are not to be outdone by the "world's best" cheddar cheese, hobby garden or seed rice, or even the "world's greatest" waterfall, harbor, gold mine, battleship, oil field, rodeo clown, roller coaster or chicken, among many others.

While some markers date back centuries, they proliferated in the 20th century, meant to capture the attention of traveling Americans who had hit the road for the first time in their new cars. The markers brought business and tourism to out-of-the-way towns. Today the roadsides and public squares of America are replete with markers that fulfill their most basic purpose, offering a simple, often sterile recounting of an interesting moment in place and time.

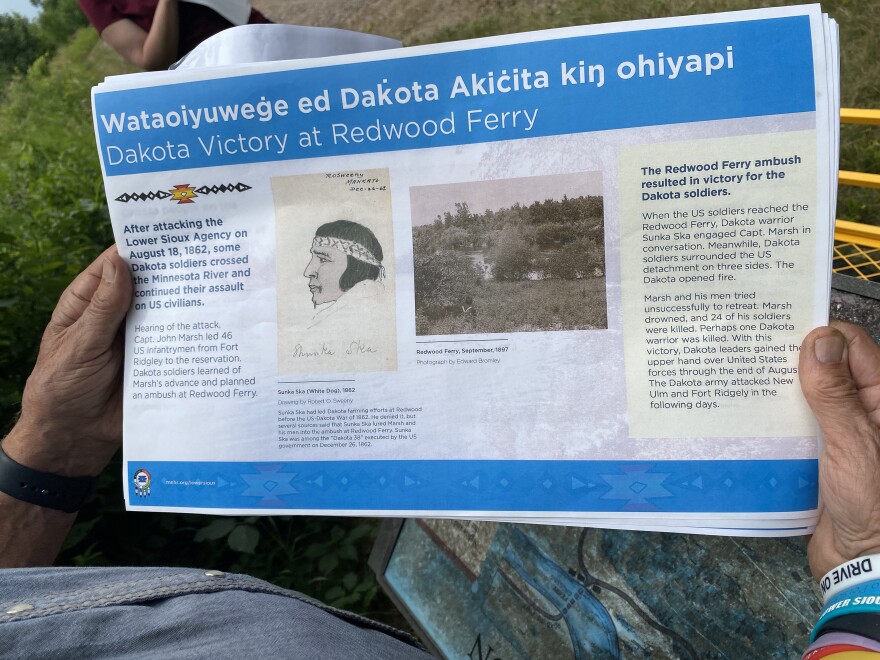

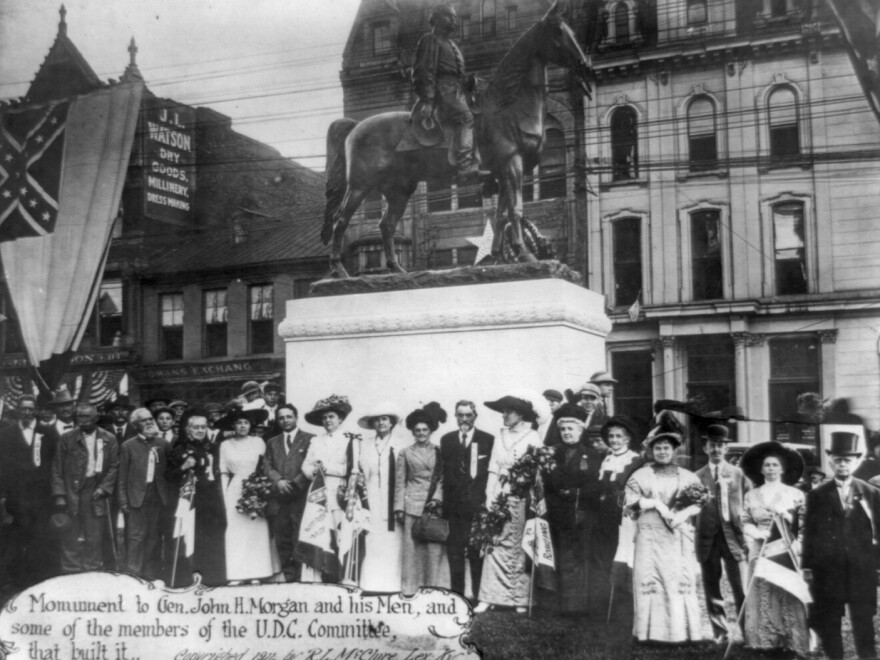

But over the past century, many markers have also become symbols of the country's dark and complicated past, in some cases erected not to commemorate history but to manipulate how it is told, NPR found.

Copyright 2025 NPR

Loading...

Loading...