Rose Wilder Lane didn’t pine for De Smet, South Dakota. “I hated everything and everybody in my childhood with such bitterness and resentment that I didn’t want to remember anything about it,” she wrote.

But she did remember. And the memories she dredged of her early childhood in Dakota — as a writer and a tutor to her immeasurably more famous mother — helped mythologize the drought years of poverty, diphtheria and toil that drove her itinerant family further again from the Big Woods of Wisconsin they'd left behind to trace a hungry trail across the Midwestern plains from one hardscrabble patch of indifferent earth to the next.

Rose was born in December, but Laura Ingalls Wilder named her daughter for the prairie rose, “because she symbolized a hope and longing,” wrote historian William T. Anderson, “that all of Dakota could be as flowerful as the mass of wild roses that covered the land during the month of June.”

She was born in a claim shanty north of De Smet, the first child of Laura and Almanzo. (Her only sibling was an infant brother who lived till his twelfth day.) Her parents were already in debt. They’d lost that year’s wheat crop to a hailstorm. The following year both parents came down with acute diphtheria. Almanzo couldn’t take the time to convalesce, then suffered a stroke that left him diminished for life by periodic paralysis of the feet and hands. Then the drought years. All that well-known Little House woe was the stuff of young Rose’s childhood in Dakota. Diehard fans might recall some details from The First Four Years.

There were brief interludes in Spring Valley, Minnesota where the family boarded with Almanzo’s family, and the Florida panhandle at the homestead of Laura’s uncle Peter. Then back to De Smet in time for the Panic of 1893 and another migration, this time into the Ozarks near Mansfield, Missouri — at a place they called Rocky Ridge — where the plow could earn them enough to get by till Laura mastered the pen.

At seventeen, Rose was done with all that — De Smet, Spring Valley, Rocky Ridge, all the quaint place names that were signifiers for struggle — or so she thought. “My father and mother were courageous, even gaily so,” she recalled. “They did everything possible to make me happy, and I gaily responded with an effort to persuade them that they were succeeding. But all unsuspected, I lived through a childhood that was a nightmare.”

She’d gotten her first glimpses of a bigger world boarding with her aunt in the relative metropolis of Crowley, Louisiana while she attended high school. She excelled in Latin and stumped for Socialist Party presidential candidate Eugene Debs. After high school, she left home to be a girl alone in Kansas City, working a job as a telegraph operator, but no 9 to 5 could hold her down. “Making the best of things,” might have worked for her long-suffering mother, but for her it was “a damn poor way of dealing with them.”

“If I’d ever made the best of things,” she wrote, “my God, I’d be stuck in Mansfield yet.”

A failed strike against Western Union interrupted her job in Kansas City. She spent some time back in Mansfield, then Indiana, before moving to San Francisco where she met and married a journalist named Gillette Lane, whose last name she would keep for life.

Gillette wasn’t a make-the-best-of-things sort either. He brought Rose along on a hustler’s tour of the Midwest, pitching his services as a town development promoter-for-hire or newspaper subscription salesmen. Eventually they worked their way east to New York where they camped at the Waldorf Astoria, then back to San Francisco. Theirs wan’t a happy marriage. Rose became depressed, even suicidal. “It is really much better to be killed quickly than little by little,” she wrote. They split in 1915.

She wouldn’t marry again. Marriage, she wrote, was “the sugar in the tea that one doesn’t take, preferring a simpler, more direct relationship with tea.”

She made forays into journalism leading to a position at the San Francisco Bulletin, where she pioneered a series of serial biographies of famous contemporaries like Henry Ford, Charlie Chaplin, Jack London and Herbert Hoover. These weren’t high-minded literary works. From the start, Rose flaunted a hustler’s casual regard for the facts. Chaplin sued. London’s widow objected. Even Hoover, who she adored and eventually became a fan, attempted to quash his own bio.

She wrote romantic serials in which female protagonists negotiated the tension between their marriages and careers. Her The City at Night series took readers into the opium dens and after-hours cabarets of San Francisco, introducing them to prostitutes and criminals.

She developed a lifelong friendship with Bulletin editor Fremont Older, a staunch political progressive who fought, for decades, for the release of labor leaders Thomas Mooney and Warren Billings, who were convicted of bombing the San Francsico Preparedness Day parade on the eve of World War I. She hung out with Russian Revolution hagiographer John Reed, The Masses editor Floyd Dell, and feminist writer Jane Burr.

When the Bulletin went under, she ended up in New York, where she sold A Bit of Gray in a Blue Sky — her story of Cher Ami, a homing pigeon that helped save the “Lost Battalion,” encircled by German forces in the Argonne Forest — to Ladies’ Home Journal.

In the 1920’s, she criss-crossed Europe working as a freelance foreign correspondent for the Red Cross Publicity Bureau and other outfits, where she became part of a loose knit sorority of young American women documenting, and doing what they could to alleviate, the suffering caused by the War.

In Albania, at the top of a steep switchback road called “the Ladder,” high in the Dinaric Alps, she found “a limestone country practically without soil, where the inhabitants lived in stone houses indistinguishable from the landscape.” Biographer William Holtz writes, in The Ghost in the Little House: A Life of Rose Wilder Lane, that in this stark environment, “she found American women, far from home but marvelously competent, dealing with the civil devastation left by the Austrian army. Surrounded by starving and homeless children, an incompetent government, and disbanded soldiers turned brigands, these women met daily crises and still managed to turn an old harem into an American home in which every night they dressed for dinner.”

Did Rose see something of her resilient pioneer mother in these American women with their flinty compunction to do good? Maybe she saw Laura, or “Mama Bess” as she called her, in the Muslim peasants of Albania. She wrote to Mama Bess of an alpine warrior that “slings a Mauser across his shoulders, takes the chain of a donkey in his hand, and walks straight up what you would call an utterly unclimbable mountain, literally dragging the weight of the donkey behind him, and singing as he goes… They don’t seem to know what it is to be breathless.”

Her time in Albania would inspire another serial: The Peaks of Shala: Being a Record of Certain Wanderings Among the Hill-Tribes of Albania. Her introduction was characteristically self-effacing: “I would not have this book considered too seriously. It is not an attempt to untangle one thread of the Balkan snarl; it is not a study of primitive peoples; it is not a contribution to any part of the world’s knowledge, and I hope that no one will read it to improve his or her mind… It is simply a fragment of this great, various, and romantic world, sent back by a traveller to those who stay at home.”

Peaks reads like a casual journal by a writer in awe of “a land where a twelve-inch trail is to the people what the Twentieth Century Limited is to America.” Albania would exercise a permanent hold on her imagination. And her heart. During her travels there, she met a twelve-year old orphan named Rexh Meta who she credited with saving her life on one particularly perilous journey. She adopted Rexh’s education as a personal obligation, later helping put him through college abroad at Cambridge.

She experienced a crisis of metaphysical angst in Albania — a place where a former child refugee from Dakota could feel relatively privileged financially, but spiritually hollow — that would follow her. Years later she’d recall an encounter with a “Young Turk” in Aleppo: “We must stop submitting to God [he says]; we must stand up and fight God, as you do… Islam will die if we don’t. Islam will die if you do, I said. Yes, he said; but we must survive, we must fight, we must stop submitting to God and defy Him, fight in the western way, or The West will destroy us completely. What will it profit you to win the whole world and lose your soul? I asked him. God knows, he said. But why do I have to tell you, a Westerner, that you Westerners are right? You can’t tell me we are, I told him; because I don’t believe it.”

She witnessed mass graves in Armenia, where she travelled in the employ of Near East Relief, an American charity formed in response to the Ottoman genocide. In Erivan, wrote Holtz, “the sounds from the torture chambers kept her awake at night,” as the Bolshevik army forcibly annexed the afflicted nation into the Transcaucasian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic. “Armenia first revealed to me the inherent cruelty of mankind,” she wrote.

Europe had changed her. She wrote to her lover that, “We forget that there can be anywhere on earth that isn’t overrun with refugees and hysterical about the next war… Women come to Europe and don’t ‘go to pieces’… they just don’t fit in any more. In Europe or America.”

She sailed the Levantine Sea, traveled across the Middle East, dutifully mailed picture postcards to her grandmother Caroline Ingalls in De Smet, got lost in the Syrian desert in a Model T.

In 1924, at thirty-eight, Rose ended up back in Mansfield, where she helped her parents pay the bills. She was a far more accomplished writer than her mother at this point, though Laura had been publishing a non-fiction column in the Missouri Ruralist since 1911.

The column surveyed subject matter from marital advice to how to save on groceries in what Laura might have called a “homey” style (A Homey Chat for Mothers was a typical headline). Occasionally she discussed contemporary social issues, like how war work had changed women’s roles, or the inevitability of the women’s vote. In a column titled New Day for Women she wrote: “When at last the ‘Beast of Berlin’ is safely caged… the women are going to be largely in the majority over the world. With the ballot in their hands, they are going to be the rulers of a democratic world.”

Rose used her connections at the Country Gentleman to get Mama Bess some bylines in the pages of the popular, nationally distributed agricultural journal. And she wrote her own version of downhome tales from the farm, later published in a volume titled Hill-Billy.

She wouldn't have been oblivious to the dimestore mawkishness of the title. Genre-fiction was something, like her biographies, that she did for money.

“What I most want is money,” she wrote, “but also I do want to write something that says what I want to say.”

She had to get by though. Her lifestyle wasn’t cheap. And she struggled with what it was she really wanted to write. She lamented that on the verge of her fortieth year, “the first twenty were wasted.”

When her second installment of Ozark bumpkin stories, Cindy, went to press, she lamented that, “It is cheap, it isn’t true, it says nothing worth saying… I wrote it as a serial, for the money. I didn’t want to write it for itself.”

The vacuity she perceived in her work, a pessimism about the state of humanity she’d picked up in Europe, and a sense of alienation — both from her plebeian upbringing and her intellectual friends — led her to a crisis of ideals, and eventually to an explicitly political solution

Meanwhile, her financial ambition was a boon to her family. At Rocky Ridge, she built an English-style stone cottage for her parents and took over the farmhouse.

Then the 1929 market crash decimated Rose’s and her parents' investments.

More than ever, she generated stories inspired by material needs. When her mother’s manuscript for Pioneer Girl was rejected, she advised her to separate the section she had written on her happy childhood in Wisconsin. She helped her write and re-write this new manuscript until it became Little House in the Big Woods. The book was published in 1932, and designated a Junior Literary Guild Selection. At sixty-five, Mama Bess was on her way to literary stardom.

As Rose helped her mother edit her manuscript for Farmer Boy — an account of her father Almanzo’s childhood — she began to mine her own childhood recollections of Dakota, as well as her mother’s (of Dakota and Minnesota), for material for her own novel, Let the Hurricane Roar.

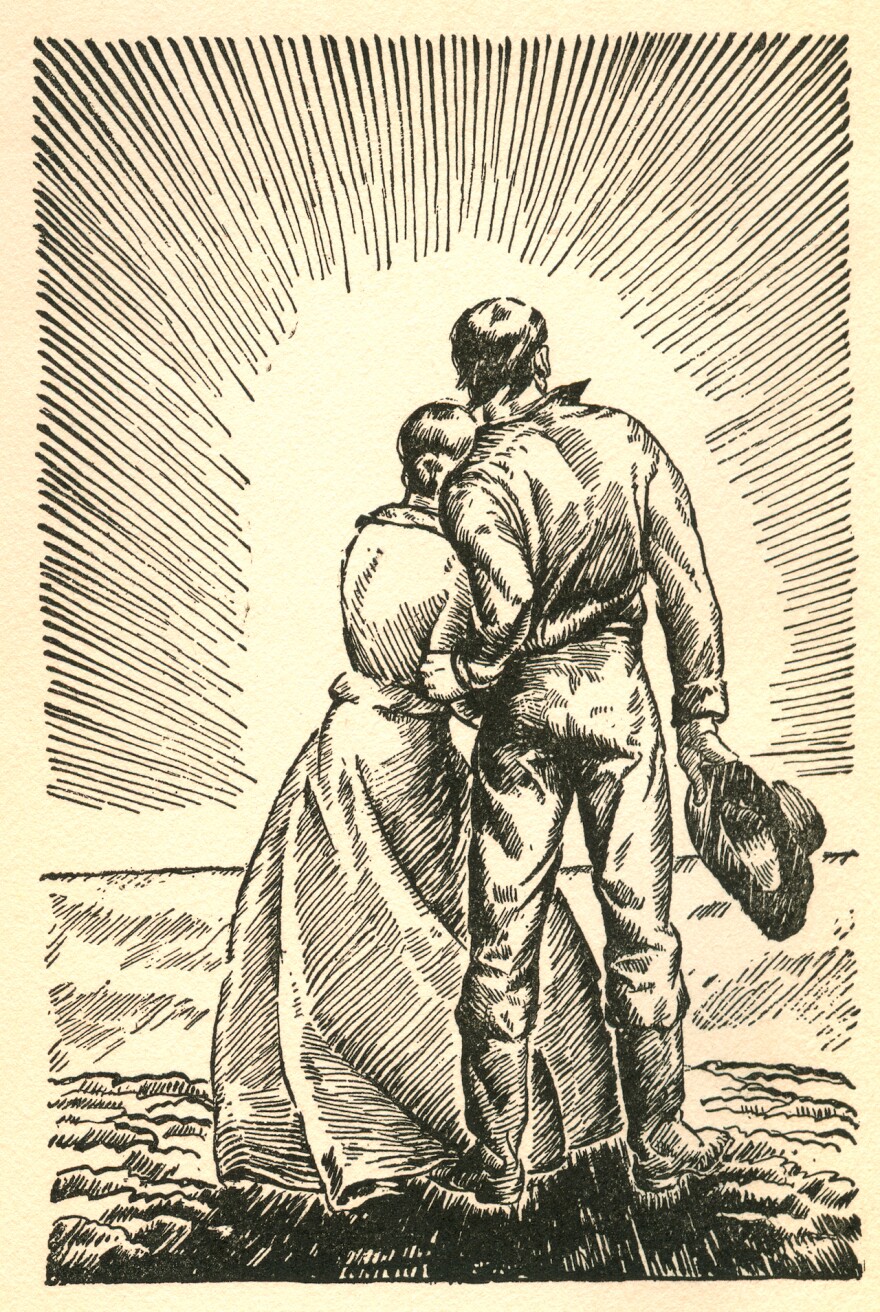

Broke again, her own financial hardship now the American norm, she returned to (perhaps idealized) memories of her pioneer parents and their stoic determination in the face of adversity. She had hated the Dakota plains and their harsh indifference to human suffering. Now that very indifference helped her mold composites of her parents and grandparents into archetypal hero-guides for a nation grinding through its own long winter.

Farmer Boy and RWL’s Let the Hurricane Roar both debuted in 1933 as unemployment rose to twenty-five percent. Hurricane — with its evocation of an Old Testament-style grasshopper plague, excavated from her mother’s memories of Minnesota — was the more timely, and written for an adult audience. (Laura’s first book to revisit the lean times was Little House on the Prairie, published in 1935).

Hurricane’s protagonists, named for Rose’s maternal grandparents Charles and Caroline, are lured westward from “the Big Woods,” by the promise of free land for those willing to work it. They move into their dugout, close to a stream they name Wild Plum Creek. Caroline gives birth to a baby boy. Charles plants a crop of wheat that grows strong and tall, “milky kernels swelling.” He runs up the tab at the dry goods store in town to start building a proper homestead.

Then an ominous cloud appears. Grasshoppers, millions of them. Part II opens with a line from Exodus: “And there remained not any green thing.” The young pioneers struggle against poverty, debt, blizzards and wolves. The writing is austere and the dialogue terse. It is her only novel that has remained continuously in print.

The Argus Leader’s review called Hurricane, “the same old story of pioneer life… that can still be heard from the lips of thousands of South Dakotans who lived through those trying times, and the writer depicts it perfectly.”

Rose’s Dakota novels — the second, Free Land was published in 1938 — would eventually be vastly overshadowed by her mother’s. (LIW’s first novel set in De Smet was 1939's By the Shores of Silver Lake.) This may be because her mother was a better writer (though some believe that Rose was essentially her ghostwriter ), or because the juvenile format jibed well with the Wilder family’s life-on-the-farm tales. Or maybe because by the time Rose published Free Land, she’d begun to consciously incorporate her politics into her storytelling, at least in the subtext.

For several decades, both Wilders were treated as important writers in the pioneer sub-genre, especially in South Dakota — maybe nowhere more than in their old home town. William T. Anderson wrote that De Smet News editor Aubrey Sherwood, “became the unofficial historian for Ingalls-Wilder lore,” already a cottage industry by the 1940’s. Mother and daughter even appeared together in Pierre, along with Laura’s sister Carrie, to present the South Dakota State Historical Society with Charles “Pa” Ingalls’ fiddle.

In 1959, the Argus Leader editors wrote that though Laura Ingalls Wilder was “a woman of distinction,” her stories “do not approach the literary heights reached by Rose Wilder Lane,” calling Hurricane “an American classic.”

By then, Rose was better known for her politics than her novels. As an individual, Rose Wilder was an altruist. In 1933, while she was articulating her opposition to FDR, who she considered “a dictator,” she unofficially adopted a fourteen-year-old orphan boy named John Turner who showed up at her door in Rocky Ridge asking for work. Later, she’d do the same for his younger brother Al, seeing to it that the boys were taken care of and educated. She was already helping her other adopted orphan, Rexh Meta, pay for his studies at Cambridge.

Rose questioned the New Deal progressivism of her old friends from the San Francisco years in letter exchanges with Fremont Older — her longtime editor at the Bulletin — and in print.

She saw the New Deal as a tool for social control — associating attempts by the short-lived Resettlement Administration to relocate struggling farmers with her recollections of Soviet-occupied Armenia and Georgia. The Depression would be a lonely time, ideologically, for a nascent libertarian, but, always the contrarian, RWL subtly wove her evolving politics into the pioneer ideal she presented in Free Land. The New York Times recommended it for a Pulitzer.

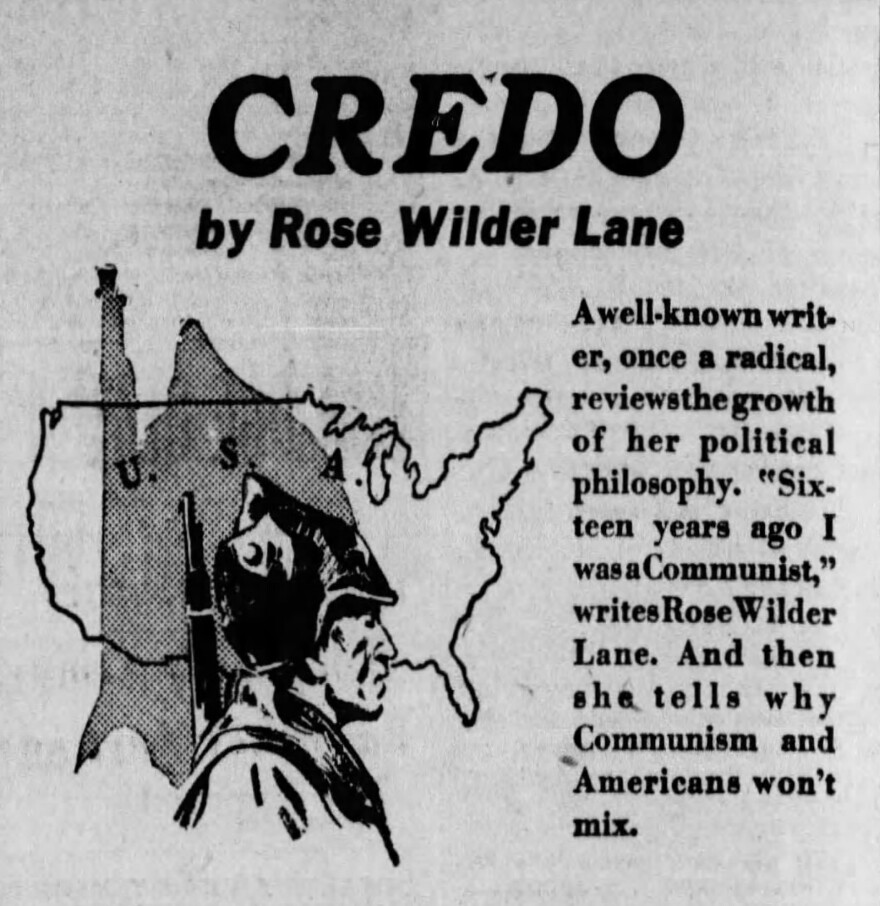

She penned a polemic titled Credo (1936) for the Saturday Evening Post. “In 1919, I was a communist,” it began. She made her case against communism as a “collectivist economic reaction” against the freedoms won (from established religion) by the Reformation and (from monarchy) by the political revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries.

In Mussolini, she saw another example of Europeans “resisting, and vitally resisting, individual freedom and the industrial revolution.” She saw America as an experiment in barely controlled economic anarchism — as an acknowledgement that, “In actual fact, the population of a country is a multitude of diverse human beings with an infinite variety of purposes and desires and fluctuating wills.” Freed from the old European caste systems she argued, anarchic American individualism was an unrivaled economic engine.

The New Deal, like the Kaiser’s Germany and Russian communism, was a reaction (“reactionary national socialism” is what she called it) to the real revolution, the American revolution of unrestrained individualism, in which “American farmers are compressed into a peasant class, subject to orders and punishments decreed by a ruling class.”

She worried that FDR’s job programs would rob Americans of the grit and self-reliance that had kept her pioneer parents going through all the pestilence and weather that Dakota could throw at them.

She was at turns alarmist (“This is an emergency… that has been acute since 1933, and it grows more dangerous hourly”) and optimistic (“Individualism has the strength to resist all attacks”). Credo attracted an audience, and was published as a pamphlet titled Give Me Liberty.

RWL is often considered — with Ayn Rand and Isabel Paterson — one of the three godmothers of libertarianism, and alternately admired, despised or mocked as such.

She was influential, at the time, in the libertarian and isolationist movements. She testified before a 1939 Senate Judiciary Committee on the failed Ludlow Amendment — which would have required a national referendum before Congress could declare war.

While Credo and Free Land both found sizable audiences, her politics and a growing, corollary paranoia gradually estranged her. She proposed a serial based on a mechanic named Charles McCrary who built an ingenious suspension bridge — for just over one thousand dollars — over the Snake River in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. With its title echoing FDR, and more recently Donald Trump, “The Forgotten Man,” would have demonstrated what a seemingly ordinary prole can do when the powers that be get out of the way. The Saturday Evening Post rejected the pitch.

She slowly transformed from the bohemian writer with communist friends to a crotchety, bespectacled right-wing eccentric with a schoolmarmish vibe. She lost old friends and made some questionable new ones. Eventually she became better known for a spat with the FBI — when she discovered they had a file on her, and fired off an editorial titled What is This — The Gestapo? — then for her books.

As the world descended into war again she wrote passionately against anti-Semitism, and entering the war. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, she supported the war but continued to oppose FDR’s domestic policies. The Discovery of Freedom, her follow-up to Credo, was published in 1943. The country may have been pre-occupied with defeating Hitler and Hirohito, but ’43 was a marquee year for libertarian literature — Paterson’s The God of the Machine and Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead are still in print. The Discovery of Freedom barely registered — selling just over a thousand copies.

For a while, she found an unlikely outlet for her ideas at a popular African-American weekly, the Pittsburgh Courier — her individualism was anathema to racial, as much as class, hierarchies. She wasn’t the only writer at the Courier to take a ride on the socialist-to-libertarian special. Praised, and published, by H. L. Mencken, over the course of his career, the Courier’s star African-American columnist, George Schuyler, went from business manager at the NAACP to a writer for the John Birch Society’s American Opinion over the course of his career. He wasn’t a complete anomaly. Other African-American writers turned anti-communist included Zora Neale Hurston and Richard Wright. But like RWL, Schuyler took a harder stance than most, even harshly criticizing Civil Rights leaders including Martin Luther King for their alleged ties to radicals. Like RWL, he would languish in obscurity in his later years. But in the 1940’s there was a place for anti-New Deal intellectuals at the Courier.

A typical introduction — that could double for an audition — from her Courier column Rose Lane Says: “There’s nothing negative in my opposition to socialism, whether it’s international (Communism) or national (Nazi, Fascist or New Deal)… I am for the capitalist society in which a penniless orphan, one of a despised minority, can create The Pittsburgh Courier and publicly, vigorously, safely, attack a majority opinion.”

She was both an optimist — she believed that, in the end, America would prevail against the forces she saw as dragging it down — and an originator of what critics would later call the “paranoid style in American politics,” opposing government rationing so fiercely that she returned, somewhat, to her agrarian roots. Well past middle age, living now in Danbury, Connecticut, she fashioned herself as a right-wing Thoreau of sorts, refusing the ration card, growing her own food to go off the grid.

As WWII gave way to the Cold War, she gave up literature altogether for politics, picking fights against perceived threats to freedom, large and small, from selective service to local zoning squabbles. Her fight against real or imagined communists may have been partially personal. Her adopted Albanian son, Rexh Meta, would be imprisoned first by the Italian fascists, then the Soviet communists that dominated his country. She sent money to his family and attempted to secure pressure for his release, but Meta would spend nearly three decades in prison. After her death, Lane’s political disciple Roger MacBride — who would run for president on the Libertarian Party ticket in 1976 — sponsored Meta’s wife and children’s emigration to the US.

As she grew older and more dedicated to the cause, she shrouded herself in a bubble of alt-politics obscurity — teaching classes at an unaccredited libertarian college founded by an eccentric radio personality named Robert LeFevre, writing many letters to newspaper editors.

In 1965, at age seventy-eight, Woman’s Day unexpectedly asked her to travel to Vietnam as a war correspondent. In her article, her admiration for the land and people of Vietnam is reminiscent of the euphoria she had expressed in Albania decades before. (“There is something in these people that isn’t explained, something that does not give up, that is not conquered.”) She characterized the fight against the Viet Cong as another in a long series of fights for national freedom, aided this time by the ultimate revolutionists, the Americans. Again out of sync with her times, she predicted a sure win over the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong.

When she died in 1968, the obituaries remembered her anti-New Deal activism, run-in with the FBI, and fringe-right experiments with off the grid living, which may be what she’d have wanted.

Her mother’s posthumous prominence hadn’t peaked yet. The Little House television series would debut in 1974, winning millions of new fans. Ronald Reagan was one. The appetite for Wilder pastorals even sparked new interest in Rose’s Let the Hurricane Roar as a made-for-TV movie and re-release retitled Young Pioneers.

Today, it’s hard to imagine a Netflix or Amazon update on Little House taking off like a prairie fire in the zeitgeist, but Laura-mania is still going strong (thanks in no small part to the Melissa Gilbert, Michael Landon one-two punch). And that means that some unquantifiable portion of Rose Wilder Lane’s prolific literary output (and the spinoffs it inspired) is very, very popular.

RWL had endured being pulled back in to the provincial orbit of Rocky Ridge, seeing her own established byline subsumed by her novice mother’s, and rejection by her cosmopolitan friends. But through the LIW oeuvre, RWL found an audience among the hayseed America she had escaped, gravitated back to, escaped again, and finally learned to admire, though mostly from a distance. If, as a political allegorist, her influence was negligible compared to an Ayn Rand, the plucky self-reliance — a quality she saw as uniquely American — she helped to infuse in LIW's Little House cast of characters made them far more recognizable than The Fountainhead's Howard Roark.

How large a role did Rose play in creating the Little House series? There are several schools of thought. Some designate her as the urbane, jet-setting ghost writer for the mother who better looked the part, some as simply editor and adviser to a self-taught folk genius. Little House adherents and detractors have ample cause to amplify or deny the role of the daughter. Somewhere in between, there’s probably an answer that neither diminishes Laura Ingalls Wilder’s accomplishment nor denies the significance of Rose’s contribution.

We know that RWL was freelancing for major-circulation newspapers in San Francisco before Laura wrote her first advice-from-down-on-the-farm columns for the Missouri Ruralist. She used her connections to introduce her mother to a national market, then rewrote her efforts to make them publishable. She developed the first series of Wilder family pastorals through her Hill-Billy serial set in the Ozarks. She took her mother’s original autobiographical manuscript and shaped it into the episodic form that became the Little House series, then wrote and rewrote her mother’s revised episodes.

“What Rose accomplished was nothing less than a line-by-line rewriting of the labored and underdeveloped narratives,” wrote biographer Holtz. “Her mother would deliver her own best effort in full expectation that Rose would work her own magic on it.” Holtz offers several comparative sections of the original manuscripts juxtaposed with RWL’s revisions. The improvements are as undeniable as indispensable. If Laura’s voice evinced more firsthand knowledge of the subject matter, Rose the technician understood context and continuity. Far from simple edit jobs, she often spun several chapters out of one to create a more coherent story line. She invented expository dialogues that hadn’t been there. She cut tedious or superfluous material altogether.

This wasn’t new for Rose. She was already ghostwriting for adventure writers Frederick O’Brien and Lowell Thomas when Mama Bess brought her the original manuscript. But she dedicated herself more fully to “ghosting,” as she called it, for her mother. Though she continued to produce her own work, gradually her mother’s work subsumed her own efforts.

Little House may have offered her a rare project where her liabilities became an asset: her casual relationship with truth had caused some trouble for her earlier biography series. A little dramatic license could’t hurt a children’s series presented as autobiographical fiction but largely based on fact. Her independent attempts in the pastoral genre had been as contrived as much of her other work — which she often considered beneath her. For both Rose and her mother, the motivation behind the Little House series was monetary as much as artistic, but here Rose dealt with intimately familiar material. She could impose the formulaic structure she knew — as a practiced genre-writer — that publication would require, without diminishing its rugged farm-to-coffee-table authenticity.

Little House was a project born of the Depression. Mama Bess presented Rose with the pioneer girl manuscripts after the crash that wiped out everything the Wilders had. At a low point in her life, the child refugee from Dakota turned globe-roving citoyen du monde would transport herself mentally, sometimes physically, to a geography and past she’d resolved to put permanently behind her. She couldn’t have known that the project would monopolize her creative energy for over thirteen years.

Rose was nagged by her belief that the New Deal would rob Americans of the wherewithal that kept her mother keeping on through the long winters, or the drive that had propelled Rose herself from an impoverished daughter of Dakota to a Pulitzer contender. The vast majority of the country never embraced her politics — though communism’s demise in Eastern Europe, including her beloved Albania, might be seen as a partial, posthumous vindication — but Americans do like fighters and Rose helped her mother launch an enduring cast of flower-print dress and suspenders-wearing can-doers from her own personal memory banks into the common culture.

The Wilder duo created an archetypal American everywoman, as relentless in her pursuit of land and freedom as the grasshopper swarm in Let the Hurricane Roar: “No matter what they came to, they went right on… Crawling west. They crawled straight into the creek, never stopped. They crawled into it and drowned till they clogged it up and the others crawled across on their backs.” The metaphor was RWL's, but she would have limited the insect/human comparison to the pioneers’ determination. People were not an undifferentiated swarm. “Plants and animals repeat routine,” she wrote in Credo, “but men who are not restrained will go into the future like explorers into a new country, and great numbers of explorers accomplish nothing and many are lost.” That was cold, Darwinian fact — the recently published, unedited Pioneer Girl manuscript documents some of the lost explorers’ ends. The upside was ostensibly that free people would learn from their forbears' mistakes and find ways to prevail.

Though RWL escaped the small world of Rocky Ridge and built a name for herself as a self-educated female journalist before women had the right to vote, she had openly worried that she was wasting her talents, didn’t know what she wanted to say. That fear was compounded when she ended up broke, back at Rocky Ridge, and “ghosting” for others. An outspoken, ornery individualist — ironically, her most lasting artistic contribution was achieved through sublimation of self.

But RWL was a tangled web of apparent contradictions like humans are supposed to be. Publicly, she railed against the welfare state, while privately she provided generous support to her unofficially adopted children and grandchildren, making arrangements to continue aid even after she died. She was a nineteenth-century born professional woman and divorcee who ignored conventional gender, sexual and social mores — to the consternation of some of the citizens of Mansfield, Missouri — who wrote the Woman's Day Book Of American Needlework. She was the right-wing white lady writing in the pages of an African-American owned paper that “copies of the Courier could be used to educate whites” out of their ignorance and false sense of superiority.

For all her contradictions, the apparent friction between the fierce individualist and her self-sacrifice as the lurker in the Little House may be less fraught than it seems. RWL’s wasn’t a Great Man (Woman) brand of individualism. Always self-deprecating, she was similarly modest in evaluating the pioneer stock she sprang from. “The pioneers were by no means the best of Europe; in general they were trouble makers of the lower classes, and Europe was glad to be rid of them,” she wrote.

As a class — a quantity RWL had no use for, and didn’t believe existed in America — Europe may have been better off without them, but as a myriad of subtly unique human beings with their own thoughts, defects and desires, maybe they were better off unmoored from the Old World’s geographic, economic and social restraints. Given a chance, maybe even the rabble could thrive. History might forget their names, like it’s mostly forgotten hers, but that doesn’t make them nameless.