Of the Missouri River’s full 2,341 miles, today only 100 approximate the natural reaches experienced first by the Sioux, Pawnee and Ponca and later by French and Anglo expeditioners. In the 39- and 59-mile stretches between Pickstown, SD, and Sioux City, IA, the riverscape shifts with braided channels, capricious sandbars, and ungovernable snags that delight and challenge kayakers and canoeists.

Within the 59-Mile District of the Wild and Scenic River, between Yankton and Vermillion, lies Goat Island. Accessible only by watercraft, Goat Island is 3-miles long and a quarter-mile at its widest. The fine sand and loamy soil manifest expansive sandbars, sleepy backchannels, and a dense forest of old-growth cottonwoods with profuse underbrush of red cedar, dogwood, sumac and wild grape. The island hosts deer, beaver, muskrat and turkey. Recent archaeological inventories indicate no long-term human habitation; found artifacts include a couple of old wagon wheels, fence posts and livestock wire, as well as more “non-historic” trash deposits, like beer cans and plastic water bottles.

Goat Island derived its name from the goat herd grazed there in the 1940s and 50s by Vermillion lawyer and landowner Norman “Jake” Jaquith. Jaquith also owned nearby “Jake’s Landing,” a tree grove formerly known as “Elm City,” which supplied wood as a steamboat refueling stop. Near the upper end of Goat Island, on the Nebraska side, lies the ribs of the North Alabama steamboat, which sank after hitting a snag on October 27, 1870. In the 1970s and 80s, cows foraged the island, ferried over by Nebraska cattleman Glenn Foster, who built his hearty herd a makeshift barge out of 55-gallon drums, wood, and corrugated steel. In the early 1990s, an Omaha businessman posted signs on the island: “Property of Robert A. Suddick Trust.” While Suddick and his hunting buddies filed a quick-claim deed, locals tore the signs down within hours, according to Nebraska’s Cedar County News.

Neither South Dakota nor Nebraska claimed the island when filing for their statehoods in the late 1880s and the land was never surveyed by the federal government nor deeded. Notwithstanding its bovid squatters, duck hunters, and human campers, Goat Island has endured as mostly wild and free since its sandbars found permanent purchase, helped along by the closing off of Gavin’s Point Dam in 1957. Goat Island belongs to a three-island archipelago of sorts – two more large, permanent landforms include James River Island by Yankton and Gunderson Island south of Burbank.

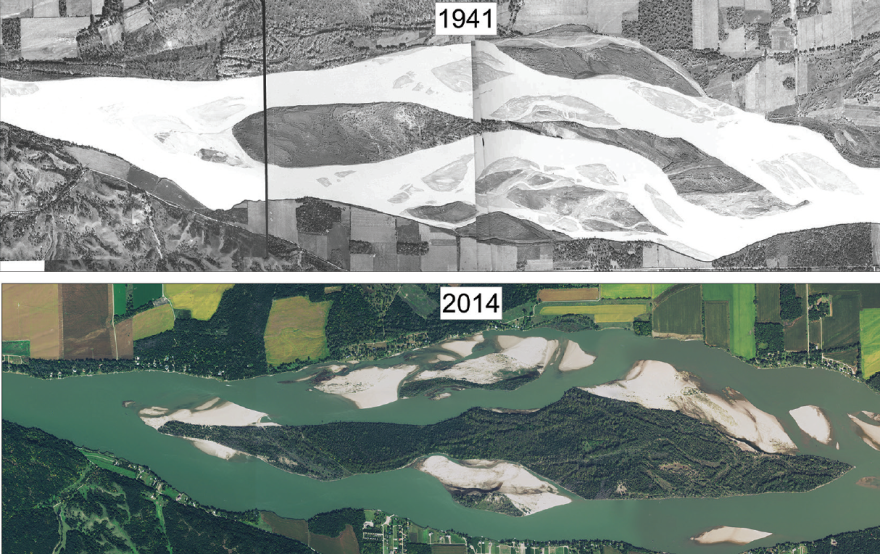

Gavins Point Dam was a steroid injection to the original sandbar complex local paddlers call “Goat.” According to State Geologist Tim Cowman, the dam closed off large Missouri flows that typically dismantle fluvial landforms. Second, the dam trapped sediment above the Lewis and Clark Lake delta near Springfield. To get said sediment back, the Missouri erodes its own riverbed below the dam in a phenomenon known as bed degradation. The riverbed, and subsequently the water level, surrounding Goat Island dropped six to eight feet since the dam went in, causing Goat Island’s banks to present 10 to 15-feet above the water level. So fortified, Goat Island withstood even the record 2011 flood.

But Goat Island’s existence above the ordinary high water mark prior to Gavins Point Dam was the crux of an official dispute began in 1999 between the Bureau of Land Management and the state of South Dakota. “The question came,” says Cowman, “who owns this island? Did the states not include the island in their Government Land Office surveys because it wasn’t there? Or because they didn’t feel it was significant enough to map? There ensued a large investigation into when it came into existence permanently.” Out came the maps to divine the island’s inception: John Evans’ 1796-97 Missouri River maps, Lewis and Clark’s from 1804, Joseph Nicollet’s of 1839. The BLM presented a 1901 letter to the General Land Office from Goat Island-occupant and prospective buyer Riley Brewer. The island’s cottonwood trees were sampled, their rings dated. Twenty years later, federal and state authorities entered into an agreement that the National Park Service would assume jurisdiction and management of Goat Island as part of the Missouri National Recreational River.

Already the area’s worst-kept secret for locals and river paddlers, Goat Island will be officially developed in the very near future. Input compiled from multiple agencies – the NPS, BLM, the states of South Dakota and Nebraska, and Clay County, SD, Cedar County, NE – leans toward minimal development that upgrades the island for activities it has informally hosted for decades. Tentative plans include backcountry campgrounds with fire rings, picnic tables, and pit toilets. Deer and turkey hunting could be limited to seasonal and archery-only. Proximate sandbars, as elsewhere along the Missouri, would be closed-off during the nesting seasons of least terns and piping plovers when necessary.

Officials say the goal is to attract more folks to the island while attempting to preserve its untouched ambiance. “Active management will bring a change to the island,” says Cowman, “but the change will actually put the island in more of a

and dogwood will get it back to a more natural form, before the dams were built, even pre-European, when floods would have overtopped the island and killed them off. I’m glad to see an agreement was reached. I think the Park Service is moving forward in a good direction.”

Grace and Harry Freeman first experienced Goat Island when they moved to Westreville from Wisconsin in the mid-1990s. “Goat was the first wild place that I came upon in this neck of South Dakota,” says Harry, who grew up near Seattle. “Some of the first times were in the winter, and it’s an extraordinary feeling because it’s just you and the river. Then landing on Goat, it’s like a kid’s feeling of excitement. You don’t know what you’re going to find.” Freemans’ three children grew up kayaking the Missouri and exploring the island. “My kids kind of grew up in a boat,” says Harry. “Now they kayak and camp out there on their own.” Grace adds: It’s a special, beautiful place. Really magical.” They support the minimal development. “Nobody owns it,” says Harry. “It’s a people’s place. And the more people who use it in a way that respects the land then the more likely that place will be protected in the future.”

Cowman, who has put in overtime with the State Geological Survey this spring monitoring water levels and prepping communities for floods, agrees Goat Island is unique. “I enjoy the serenity there. It’s a feeling of solitude to be on the island, on solid earth, yet in a place where there’s very little human activity. Even though we humans visit it now and then, it’s relatively undisturbed. You don’t find a lot of places like that in the United States that haven’t been altered significantly.”