During the coronavirus pandemic, people are finding different ways to find comfort and occupy their time while sheltering in place. Some are reading more books, others are baking bread and some are assembling jigsaw puzzles. I’ve been getting back into one of my childhood hobbies: 78-rpm records.

I don’t think it’s because the music comes from a simpler time. The records I’m listening to are swing 78s from the 1930s and 40s when the country was struggling with the Great Depression and WWII. Those weren’t exactly rollicking good times for the country. But the old records take me back to my early youth when I didn’t worry about pandemics, economic collapse or the neighborhood rabbits eating my daisies.

78-rpm discs were introduced in 1895 and eventually supplanted cylinder recordings. They were the dominant format until the late 1940s when vinyl 33 1/3 and 45-rpm records were introduced. Most 78s were 10-inches and held about three-and-a-half minutes of music. They were primarily made of shellac, which, believe it or not, is a resin secreted by lac bugs in the forests of Thailand and India.

They’re durable but also very fragile (the records, not the bugs). They were made to withstand the heavy tone arms of early phonographs. Scratches, while undesirable, don’t make 78s unplayable like vinyl records. But they break and crack easily. It’s heartbreaking when you drop a favorite treasure and it shatters into unplayable pieces. And they’re often cursed with surface noise that sounds like someone was frying bacon in the studio next to the microphone. However, a clean copy of a 78 can sound surprisingly good, especially on modern equipment.

I must have been about eight- or nine-years old when I first saw a 78-rpm record. I was at an antique auction with my dad and there was an old phonograph with a record on the turntable. I was transfixed until some kid about my age or older said he was going to play it. I was spooked and ran off. Maybe I was worried that playing the record would awaken a long-dead violinist from his eternal slumber and he’d haunt me with angry, ghostly arpeggios.

Not too much later my dad bought me my first box of 78s. I suppose it was a reward for being the only one in the family who willingly accompanied him to auctions. The box had nearly 100 records dating from 1915-1930. I guess I had overcome any fear of disturbing spirits because I’d wake up at 5 am, go to the basement and listen to as many of the records as I could before school.

The earliest 78s in the box were acoustically recorded performances of long-forgotten vaudeville stars, military bands and vocal quartets. These records had a limited dynamic range with an eerie, hollow tone that sounded like the musicians were playing in a tin can. And in a way, they were. Before the advent of electric recording in 1925, records were made by musicians and singers crowding tightly together around a large metal horn.

The later-era 78s from the box were recorded electronically and easier to listen to. They included records of hillbilly string bands, early radio crooners and dialect comedians, but my favorites were the bouncy dance bands of the late 1920s. Their music was sprightly with a hint of hot jazz as they played bizarrely infantile and ephemeral songs like “What Do We Do on a Dew-Dew-Dewy Day” and “Hangin’ on the Garden Gate Saying Goodnight, Goody Goodnight.” People complain that they don’t write ‘em like that anymore. This is not necessarily a bad thing.

All of these records took me to a strange, weird, remote and seemingly ancient world of American entertainment and culture. But as charming and fascinating as they are, I find the records quaint relics of a particular place and time. I have little interest in listening to them much anymore.

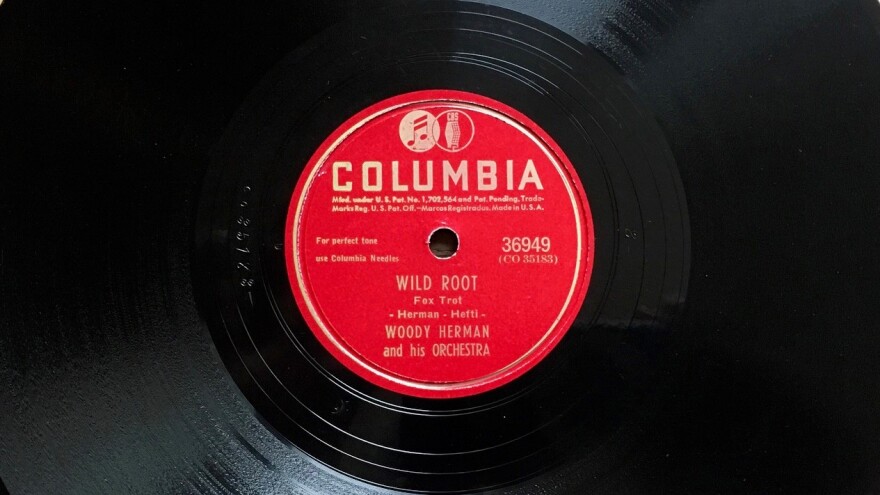

However the big band swing 78s of the 1930s and 40s, in the parlance of the time, still send me. These came in later auction boxes of records my dad bought for me. Through the years I’ve also collected more 78s from this era as people looking to get rid of these bulky records have passed them along to me. Unlike the records of the 1910s and 20s, this music still sounds fresh, relevant and alive to my ears.

I don’t know what it was in big band music that resonated so strongly with me as a kid and continues to this day. It could be the infectious rhythms or the catchy riff tunes. It could be the lively blend of saxophones and brass. Or it could be that my initial fear of 78s was correct. Perhaps playing an old big band record unleashed the spirit of some departed trombonist and it latched onto my inner being and filled me with its love of swing.

If I could travel back in time, I wouldn’t want to witness the building of the pyramids or meet Abraham Lincoln. I wouldn’t want to kill Hitler, although I'd maybe try to persuade the director of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna to accept his application. I’d want to go back to the Swing Era when big bands roamed the country like great herds of bison. I’d visit the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem to hear Count Basie, stop by the Arkota Ballroom in Sioux Falls for a performance by Duke Ellington and stomp and cheer for Benny Goodman at the Cocoanut Groove in Los Angeles.

But since time-travel technology remains elusive, my best portal to the past are the old 78 records from the days when swing was king. Many of the 78s I’m listening to have been re-released on vinyl albums and CDs, but these formats are far removed from the original records. The 78s are a much more immediate connection to the musicians playing the music. I almost feel as if Woody Herman or Tommy Dorsey could reach up through the grooves and pull me into the record. If I ever go missing, you may want to have the authorities look into this possibility.

I sometimes think about the people who first bought these 78-rpm records I’ve been listening to over the past couple months. Maybe they heard the songs on the radio or heard a favorite band play them in person and rushed to the music store to buy a copy. Perhaps they excitedly ran home and played the record over and over again. I wonder what they’d think if they knew that 75 to 85 years later someone would still be playing and enjoying their records, maybe even more than they did.

I don’t know if anyone will still be listening to these old 78s in the year 2100, long after I’ve been summoned to the big radio station in the sky. Maybe the records will all be lost in the chaos following the fall of civilization after this or some future pandemic. Or maybe they’ll be destroyed by the invading intergalactic armies of Lord Zyxxylon IV of the Tethys Moon.

It doesn’t matter if the records survive. I’m enjoying them now. Americans may have no interest in getting through difficult times with big band swing like they did during the Great Depression and WWII, but I do. In scary and uncertain times, comfort and reassurance is found in things that are constant, reliable and unchanging. I find succor in the enduring magic of swing music first preserved in wax decades ago. Everything seems right with the world when the stylus hits the grooves of a spinning 78-rpm record and the swingin’ sounds of big bands fill the air. And it’s a small price to pay if a few ghostly spirits are released in the process.