The interview posted above is from SDPB's daily public affairs show, In the Moment with Lori Walsh.

Joe Santos is with us today. We'll talk about the pain of inflation, whether or not there is cure for the pain, and how long before the pandemic-stimulus-effect wears off for more Americans.

The below is from Joe Santo's Ph.D. blog schooleddotblog.com

What Mark Sandman of the band Morphine was thinking when he wrote Cure for Pain remains the subject of much debate among the band’s enthusiasts, me included. Though chances are good he was not thinking about macroeconomic-policy prescriptions to tame the ravages of high inflation and the concomitant pain households experience when the purchasing power of their income and wealth fall dramatically over a relatively short interval of time. In any case, the cure, whatever Sandman imagined it to be, is elusive: “Someday there’ll be a cure for pain,” reads the song’s fifth line; someday is, presumably, not today—probably not ever.

When I happened on the song recently—and, no, I was not mining it for my next blog post—my mind wandered to our current state of macroeconomic affairs; maybe it was the song’s third line, “Where is the sacrifice?” Turns out, cures for macroeconomic pain are elusive, because our policy objectives often conflict, particularly in the short run, when, for example, taming the ravages of high inflation slows economic output; even though in the long run, low and stable inflation promotes economic output. This is to say, achieving macroeconomic-policy outcomes generally requires trade-offs and, thus, sacrifices: a cure for one pain introduces another. Macroeconomic-policy morphine—a so-called divine coincidence in the parlance of monetary policy—is exceptionally rare. Fundamentally, this trade-off exists because a policymaker has fewer policy instruments than mutually exclusive policy goals; the policymaker cannot simultaneously hit two mutually exclusive targets—think, price stability and economic output—with one dart—think, a short-term interest rate that moves aggregate demand and, thus, inflation and output in the same direction. We refer to this axiom of macroeconomic policy in general as the Tinbergen rule, named for one of the first two awardees of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics, Jan Tinbergen, who shared the award with Ragnar Frisch in 1969.

As Schooled readers know well, the relatively high rates of inflation the U.S. economy currently experiences are the result of strong aggregate demand—from pandemic-era fiscal and monetary stimuli—and weak aggregate supply—from supply-chain snags and the war in Ukraine instigated by Russia. In Figure 1, I illustrate the rate of inflation according the Federal Reserve’s preferred measure: a personal consumption expenditures price index that excludes food and energy, a measure of the so-called core, or underlying, rate of inflation.

While the U.S. economy is not yet replaying That Seventies Show, with high and variable inflation and low economic output, the current rate of inflation is alarmingly high. In May 2022, the measure I illustrate in Figure 1 registered a year-over-year rate of inflation of 4.7 percent, down from 4.9 percent in April. The Federal Reserve’s target for this measure is 2 percent. No matter the cause of the relatively high inflation, the instruments of macroeconomic policies, which include monetary and fiscal policies, have no effect on aggregate supply. If anything, monetary and fiscal policies shift aggregate demand, only. We could think of aggregate demand more concretely as the total amount of expenditures demanded by all sectors of the economy: namely, households, firms, governments, and foreign buyers of our goods and services. In Illustration 1, I demonstrate how macroeconomic stabilization policy—think, contractionary monetary policy instigated by an intentional rise in the short-term interest rate—shifts the aggregate demand curve to the left, causing the rate of inflation to fall from p* to its target—the bullseye pictured in the illustration—and causing the level of economic output to fall from y*. (For specifics regarding the model I depict in Illustration 1, see Monday Macro segment, “Always and Everywhere.”)

Illustration 1: Macroeconomic Equilibrium and a Shift in the Aggregate Demand Curve

Thus, according to Illustration 1, and macroeconomic theory more generally, in the short run, the cure for the pain of inflation—p* falling to its inflation target as a result of a fall in aggregate demand—is effectively a fall in output (and, typically, a concomitant rise in unemployment), a pain of a different sort. Since the start of 2022, the Federal Reserve has unambiguously communicated that it is more concerned about the risk to price stability—think, high and variable inflation—than the risk to economic output—think, recession; essentially, as of now, the Federal Reserve views high inflation as more painful than recession. For example, on Wednesday, June 30, 2022, at a conference of central bankers in Sintra, Portugal, where he was asked if reducing aggregate demand through contractionary monetary policy could tip the U.S. economy into recession, Federal Reserve Chair Jay Powell responded:

“Is there a risk that we would go too far [and instigate a recession]? Certainly there’s a risk. But I wouldn’t agree that it’s the biggest risk to the economy. The bigger mistake to make, let’s put it that way, would be to fail to restore price stability.”

No surprise, then, since the start of this year, the Federal Reserve has somewhat aggressively sought to reduce aggregate demand by raising its (only) monetary-policy instrument, the so-called federal funds rate, which I illustrate in Figure 2.

According to Figure 2, since February 2022, the Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee has raised the upper bound of the target range for this policy instrument from 0.25 percent to 1.75 percent. And the central bank has communicated so-called forward guidance indicating more rate hikes are forthcoming.

Is the cure working?

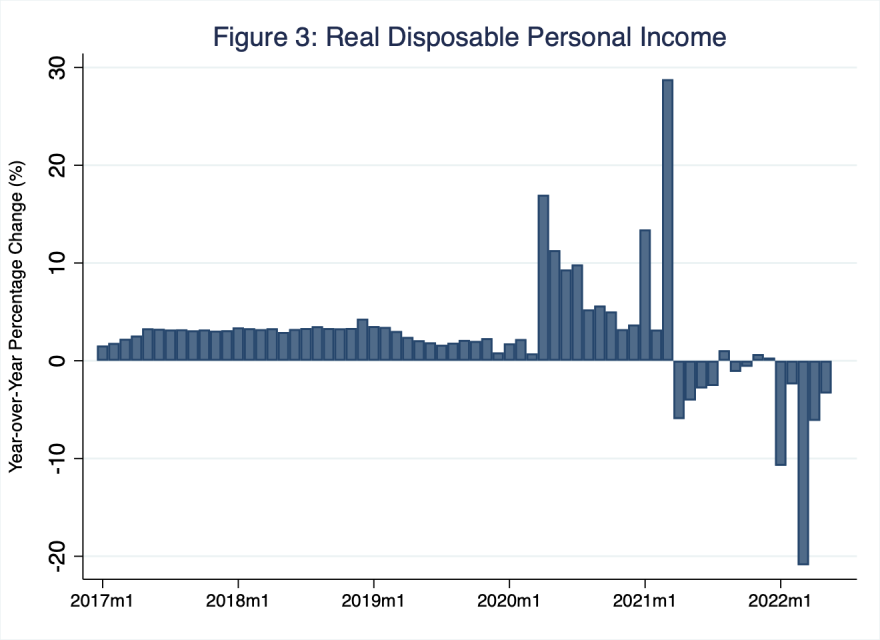

There is some evidence that the current round of monetary tightening is working. Though this evidence is rather indirect and, as one might expect from the dismal science, rather dismal. This is to say, while the rate of inflation remains elevated, economic output, broadly defined and measured, seems to be undergoing the sort of pain consistent with tighter monetary policy. So good news, the pain required to establish price stability is increasingly evident; we don’t call it the dismal science for nothing. In Figure 3, I illustrate the year-over-year percentage change in disposable personal income adjusted for inflation; we could think of positive [negative] growth in this measure—a bar rising [falling] above zero in Figure 3—as households’ budgets rising [falling], affording households the opportunity to consume more [fewer] goods and services with a given level of disposable personal income.

According to Figure 3, since early 2021, real disposable personal income has fallen. Early on, this fall was simply the result of arithmetic: during 2020, stimulus payments grew disposable income to one-off, unsustainable levels, from which disposable income has since fallen. More recently, though, a combination of high inflation and contractionary monetary policy has reduced disposable income; in the context of Illustration 1, negative supply shocks and monetary-policy-induced negative demand shocks are curing the pain of inflation, while causing the pain of recession. Incidentally, that we see evidence of these shocks in measures of output before we see evidence of them in measures of inflation is to be expected, because prices of most goods and services are rigid, as such these prices tend to adjust slowly over time—think, for example, of the time lag typically required for a rent payment to adjust to prevailing economic forces of demand for housing.

Nevertheless, at this point in the central bank’s war on inflation, the negative effects of monetary contraction on households are somewhat less apparent than we would expect all else equal. This is because for much of 2020 and 2021, all else was not equal: on the contrary, the personal saving rate was exceptionally high for a time, thus buttressing household balance sheets in ways that have, to some extent, allowed households to withstand the current high inflation and monetary contraction. In Figure 4, I illustrate the personal saving rate, which measures the share of household disposable income that households save each month.

As Figure 4 illustrates, the household personal saving rate in the years leading up to the pandemic registered about 7 percent. However, during the pandemic, thanks to rounds of stimulus payments that federal and state governments paid directly to households, combined with pandemic lockdowns that effectively reduced household expenditures (on services most notably), the personal saving rate rose dramatically; the rate peaked at an astoundingly high 34 percent in April 2020. Thus, despite rising inflation, which reduces the purchasing power of household disposable income, and contractionary monetary policy, which reduces household disposable income, on average households have been able to maintain their standards of living. Though, as Figure 4 also illustrates, recently, the household personal saving rate has fallen to about 5 percent, below its pre-pandemic central tendency of about 7 percent. In this respect, household balance sheets are deteriorating relative to their pre-pandemic conditions; the average household’s ability to withstand the one-two punch of high inflation and contractionary monetary policy is weakening.

To be sure, a recent fall in the rate of real household spending is visible in even the broadest measures. In Figure 5, I illustrate real personal consumption expenditures—an inflation-adjusted measure of all goods and services consumed by households; here I track the year-over-year percentage change in the measure, which I disaggregate into services (red) and durable goods (green).

According to Figure 5, overall growth in real consumer spending is falling. Though growth in total spending and spending on services remains positive, the growth in spending on durable goods—think, couches and stationary bikes, for example—has turned sharply negative. Indeed, growth in real consumer spending on a month-to-month basis from April to May 2022, which Figure 5 does not explicitly reveal, fell by a relatively large 0.4 percent. Decelerating and declining household expenditures matter a lot, because consumer spending comprises roughly two thirds of gross domestic product. Put differently, any change in consumer spending weighs relatively heavily on total spending, because consumer spending comprises such a large share of total spending.

A recession is how you know the cure is working.

Increasingly, it seems recession—a phase of the business cycle we define as a “significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and lasts more than a few months,” according to the National Bureau of Economic Research—may be the operative word to use to describe the current U.S. economy. As Schooled readers know well, one way to visualize the business cycle and, thus, where the economy is relative to recession, is the output gap, the difference between actual real GDP and potential real GDP—the level of output the economy would achieve if it were operating at full capacity. Generally speaking, a negative [positive] output gap reflects an economy that is operating below [above] its potential. A recession induced by a monetary contraction is loosely characterized by a negative output gap. In Figure 6, I illustrate the output gap.

According to Figure 6, just prior to the pandemic, the U.S. economy was operating at very near its full capacity; the output gap essentially closed in the third and fourth quarters of 2019. Then, the pandemic induced a short but very acute recession; correspondingly, the output gap grew deeply negative. Since then, the U.S. economy has recovered, approaching its potential output from below and, thus, shrinking the output gap, until now. In the first quarter of 2022, a typically robust sign of recession emerged: the output gap reversed course, growing more negative; in Figure 6, I illustrate this pattern with the red bar on the far right. To be sure, in the first quarter of 2022, real GDP growth registered an annualized rate of negative 1.6 percent. And, as of July 1, the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta GDPNow model forecast for real GDP growth in the second quarter of 2022 registered an annualized rate of negative 2.1 percent.

Seems the cure is well underway; prepare for the pain.