This article was produced in cooperation with the Pulitzer Center, where Jordan Rusche is a 2022 reporting fellow.

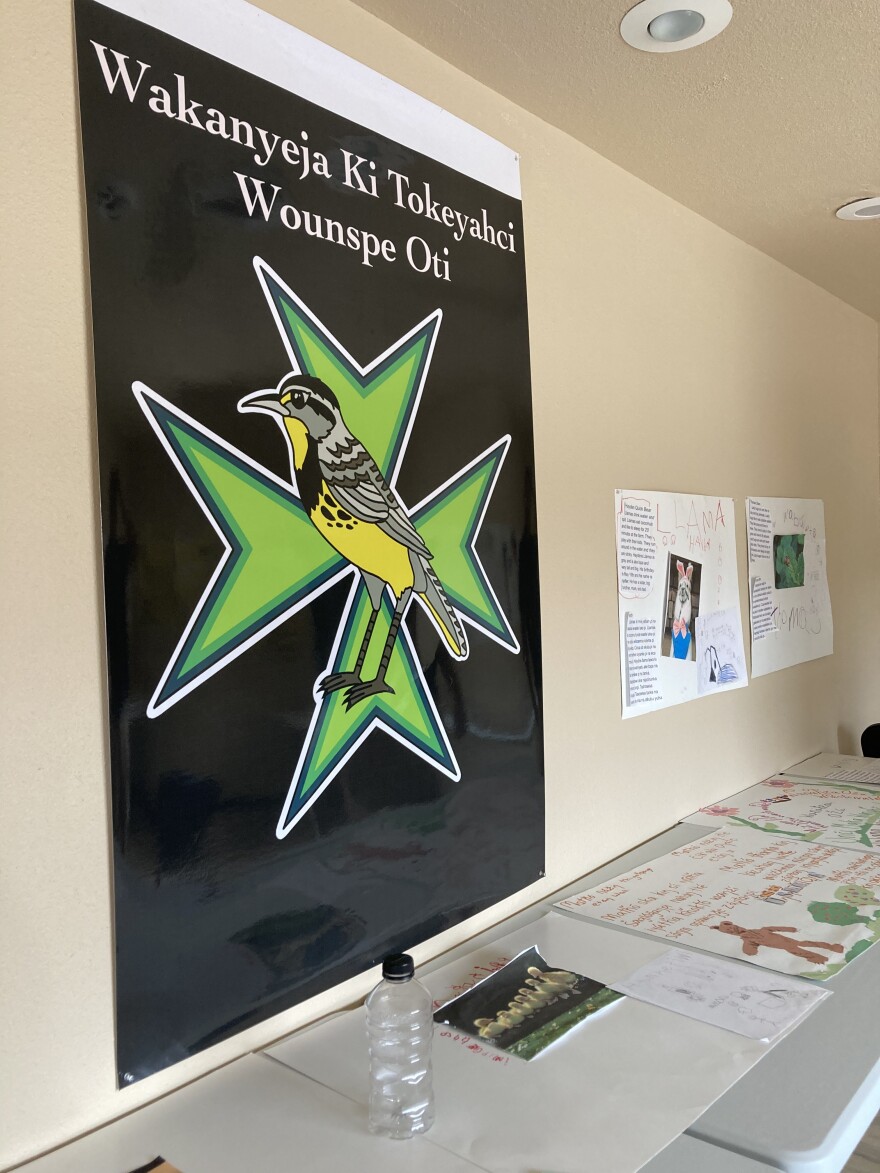

The Wakanyeja Tokeyahci Lakota Immersion School building is small, but it’s a step up from its former single-room classroom at the Boys and Girls Club in Mission, South Dakota, on the Rosebud Reservation.

Founder and director Sage Fast Dog and his employees have spent the summer cleaning and preparing the building, which is equipped with classroom spaces, a kitchen, and an open activity area, for when students return in the fall.

Wakanyeja Tokeyahci is one example of how both educators and Indigenous groups in South Dakota are fighting to better represent Native American history, culture, and values in the state’s education systems through teacher training, immersion schools, and other programs.

Wakanyeja Tokeyahci School: Is It Working?

Fast Dog, who is Sicangu Lakota, started the school in 2020 after working for the Todd County School District for 13 years. He said that growing up, he didn’t think he would be able to open or run his own school.

“Someone else, not me, can open a school,” he said. “It has to be someone else. South Dakota has to open a school for it to be legit or for it to be OK.”

But after seeing other examples of successful immersion schools, Fast Dog realized how a community-based, traditional education could help Indigenous students connect with their identity, as well as address what a lack of Native American representation can mean for non-Native people.

“If I go into any town in South Dakota, nobody should look at me different,” he said. “They should be accepting of me when I go into their town, but if you look at me and judge me because of the way I look and the way I talk, then their systems failed to educate who we are as people.”

He added that having schools like these makes it more difficult to further erase the culture of the Oceti Sakowin, the collective name for the nine tribes in South Dakota.

“If you think we’re going to go away, and you know we’re going to go away, and we’re out of sight, out of mind, it’s easy for you to manipulate us,” Fast Dog said. “It’s easy for you to get rid of us. … As if you can un-Lakota a person and plug them in to be someone else. We know that’s not healthy. It’s like when you ‘kill the Indian and save the man,’ you just kill the person.”

Wakanyeja Tokeyahci, which has 20 students from 5 to 7 years old, focuses on using Lakota culture as a background for typical elementary school lessons, along with teaching students about their own identity and relationships with others.

Immersion Schools Offer New Opportunities

Fast Dog’s school is just one opportunity for more traditional education for Indigenous students in the state. Canyon Lake Elementary School in Rapid City recently began the Lakota Language Immersion Program, where students are instructed entirely in Lakota.

The chance to learn about and express their culture has made many students more confident in their identity, according to Valeriah Big Eagle, whose son is one of these students in the immersion program.

“His culture and his language (are) going to serve as a protective factor for him,” she said. “When he is in the face of racism, he is going to be just fine because he knows who he is and where he comes from.”

Big Eagle, who is Ihanktonwan Dakota/Nakota, was part of an Indigenous education task force that helped get the school district to form the immersion school, which opened in fall 2021.

In that time, she said she has already noticed a difference in how her son behaves and learns compared to her other two children at his age, who did not receive the same kind of culturally immersive education.

“We can have conversations, like he is so smart. He can talk about politics,” Big Eagle said. “He is so smart in the way that he even goes about things in his own learning.”

Well aware of the benefits of immersion schools, educators across the state are trying to integrate more Indigenous culture and teachings into their education programs, especially in public schools with higher populations of Indigenous students.

The Wóokiye Project

The Wóokiye Project is one program that helps train and support teachers in using the Oceti Sakowin Essential Understandings and Standards in their lessons. The OSEUs are concepts that promote the inclusion of Native American traditions and values in mainstream education.

The program, which began in 2020, has five pilot schools and 28 teachers from across the state. These teachers attend monthly meetings to track and support their implementation of the OSEUs and an annual Wóokiye Teacher Conference to update lesson plans and discuss new teaching material.

Elverda Little Dog was one of the educators attending this year’s conference. She serves as an in-school suspension coordinator for Wakpala Public School in Wakpala and helps new teachers learn to use the OSEUs in their lessons.

“We were a pilot school last year, so when we get new employees, I go over and teach them all about the seven values, how we use them at the school, and it helps,” she said.

Michael Vasilie, a music teacher from Georgia Morse Middle School in Pierre, also attended the conference. He said using OSEU standards in his classes introduces students to the parts of history that are still present in the state today.

“This is humanity, and learning it from a very unique Lakota event is good, but it is also good, especially for kids who are not of an Indigenous background, to understand there is timeless wisdom of people who lived here, and didn’t just live or survive, but thrived here hundreds of years before we rolled in,” he said.

Higher Education

K-12 educators are not alone in their efforts to improve Indigenous representation in the state. Some universities are also incorporating more support for their Native students’ identities into their programs.

One example is South Dakota State University’s Native American Nursing Education Center (NANEC) in Rapid City. NANEC advises Native American nursing students on classes, scholarships opportunities, financial aid and other services. The center also helps students with other needs they may have, like finding childcare services or housing while they are getting their degree.

Big Eagle serves as diversity outreach and engagement coordinator at NANEC. She said having support systems rooted in the students’ culture and heritage helps them feel better represented and can better connect some with their identity as Indigenous people.

“Not all of them know who they are and where they come from, and it’s not their fault,” she said. “We let them know that. We don’t want them to be ashamed, because that was the plan of the forced assimilation and colonization of this country.”

NANEC also incorporates Oceti Sakowin culture into their programs. The center hosts Wohanpi na Wounspe (Soup and Learn) each month, bringing in Lakota speakers to discuss cultural education, awareness, and Lakota values in the program.

Big Eagle added that nursing ethics and values and the seven Oceti Sakowin values — gratitude, humility, wisdom, honor, fortitude, courage, and generosity — already have significant overlap.

Beverly Warne, an Oglala Lakota elder and mentor at NANEC, has worked in the nursing field for 60 years. She said these kinds of programs can give students the tools to bring about change elsewhere.

“What I do here is really gratifying to see these students growing and developing into empowered change agents,” Warne said. “They all can do it, and they’re doing it here in Rapid City and wherever they’re from. … I think education is powerful, and they know that now. It’s why they’re here.”

Native Americans make up 8.5 percent of South Dakota’s population and are the state’s largest racial minority. The state is also home to nine federally recognized tribes.

Though many South Dakotans, both Native and non-Native, still face obstacles, they have made strides in improving Indigenous representation and continue to fight for the preservation of Oceti Sakowin culture to educate a new generation of South Dakotans.