Ah, the lifespan of a fact.

What is it, that lifespan?

In Donald Trump’s world, it’s not very long, if it exists at all.

Our 45th president wasn’t the first American politician or even the first one in the White House to bend, break and completely ignore the facts. He just took the process to new heights, turning the assault on facts and the truths they can present into an underhanded art form.

There has probably never been a president quite like him in that regard.

Others have tried, of course, sometimes in very creative ways: “There is nothing going on between us,” Bill Clinton told top aides when asked about his affair with Monica Lewinsky.

“There is no improper relationship,” Clinton told PBS newsman Jim Lehrer in answer to the same question.

But how could that be, when there was so much evidence to the contrary? Well, it depends, Clinton said at the time, on the meaning of the word “is.” In the present tense of, “is,” Clinton apparently was telling the truth. At that time he said what he said, it was factual. If the verb had been used in the past tense, “was,” however, well, then it wasn’t true at all.

A lie that seems almost charming in comparison

Beyond that infamous dodge, Bill Clinton simply lied when he looked into the camera and told the American people: “I did not have sexual relations with that woman … ”

I suppose that depends on how you define “sexual relations.” But most rational, honest people would call what happened to be sexual relations and what Clinton said to be a lie.

Even so, when it comes to outright lies, no president in my lifetime and maybe of all times can match Trump.

It would be difficult to know where to start in listing Trump’s lies. But it’s hard to beat “I won that election by a landslide.”

That one makes the whole “is” or “was” argument seem almost charming by comparison. And the advantage of Clinton’s lies about the, um, improper physical relationship he had with Lewinsky was that they weren’t aimed at overturning a legal-and-fair presidential election, obstructing the peaceful transfer of power or encouraging an attack on the U.S. Capitol.

But how did I get so far off track? Call it an old-guy’s side road, the sometimes-scenic byway of digression that in this case now leads back to a Black Hills Playhouse production called The Lifespan of a Fact.

To get to the Playhouse down in Custer State Park, you follow an actual scenic byway, a geographic digression of delight. So you’re in the right mood for artistic entertainment when you reach the historic grounds of the playhouse, founded in 1946 in an abandoned Civilian Conservation Corps camp just down the hill from Center Lake.

A hike, some sandwiches and a play about facts and the truth

Center Lake exists because of the dam constructed by CCC workers in the mid-1930s. They also built some of the buildings that still stand at the Playhouse complex, although the current theater wasn’t built until 1955.

The Playhouse facilities have been much improved since their early days, of course. But the charm of the place remains, especially with a pleasant hike to a Center Lake overlook and sandwiches near the water as a prelude to the play.

I went to The Lifespan of a Fact with my wife, Mary, a retired journalist who has been called upon to write reviews this summer of Playhouse productions. She thought I’d enjoy this one, so I tagged along. And she was right. I liked it a lot.

The play is based on the true story of a gifted writer named John D’Agata, who published a book of essays in the early 2000s that caught the eye of editors at Harper’s Magazine, which is a pretty good eye for a writer to catch. Harper’s asked D’Agata to write an essay for the magazine, in this case about the suicide of a teenage boy in Las Vegas and the cultural realities around such a terrible loss.

The essay ultimately was rejected by Harper’s Magazine because of D’Agata’s loose approach to the facts. Later, a magazine called The Believer published the essay, but only after a long — years long, apparently — and often-excruciating series of revisions and exchanges between D’Agata and fact-checker Jim Fingal, who was working as an intern for The Believer.

When attention to detail collides with a loose approach to facts

After the piece was published, D’Agata and Fingal wrote a well-received book about that experience. The book was adapted into a play that mixes humor with a thoughtful examination of facts, accuracy and the meaning of truth.

The play shows Fingal finding problems with accuracy throughout D’Agata’s essay. And while Fingal is initially intimidated by D’Agata and restrained in his criticisms, he comes to argue more and more forcefully about every questionable detail. Sometimes he nitpicks to the point of being obsessive but in many cases makes valid, even crucial arguments in the defense of facts.

D’Agata, meanwhile, is portrayed as a writer with great skill and a drive to examine the human experience through storytelling, but also as one who plays loose with the truth as it is found in facts. He is often cavalier about the importance of details that seem essential, arguing that they sometimes get in the way of his art and the larger truth he’s trying to explore.

Caught in the middle is an editor for The Believer, who must deal with obsessive behavior on both sides and find a reasonable way forward to publication.

Not the journalism world we lived in

The play is funny and somber and elucidating, all of which were reflected in Mary’s thoughtful review.

Seeing the play also inspired a couple of old journalists like Mary and me — I being the older of the two — to reflect on our own experiences in journalism, which were only slightly similar to those portrayed in the play.

Neither of us has ever known a newspaper reporter who would have intentionally mishandled the factual details like D’Agata did. No good reporter in our journalism experience would have knowingly written something, minor or major, that the reporter knew was false.

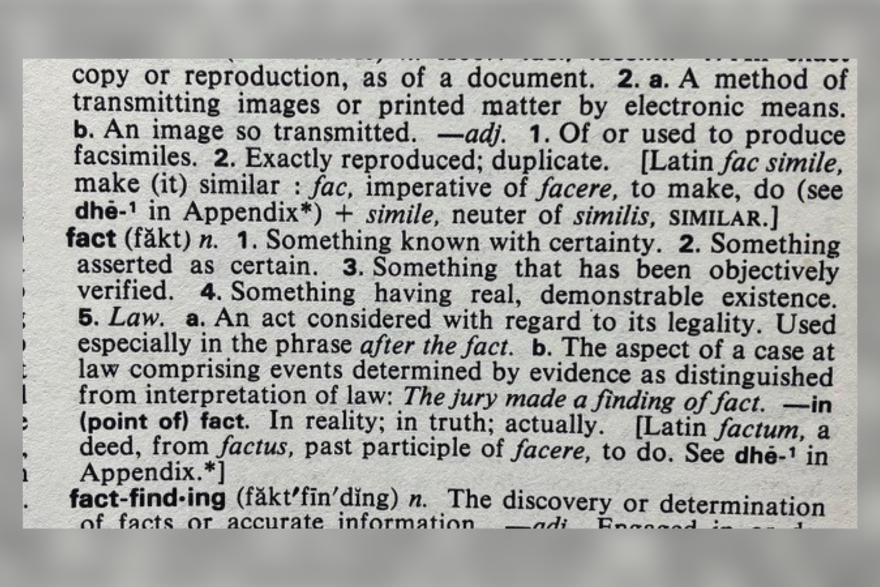

Facts matter in our business, because they are the building blocks of truth. And news careers rise and can fall on the way facts are handled.

Once when I was near the end of my full-time newspaper career, a much-younger reporter criticized me for being “afraid to tell the truth” in my news stories. I told him it wasn’t my job to tell the truth. It was my job to present the facts. And, I said, if I did that honestly and fairly and accurately, the truth would present itself.

That doesn’t mean a journalist can’t write from what a newspaper editor of mine liked to call “a position of authority.” That means you have done enough research, asked enough questions and know the story well enough to write from a well-informed understanding of the facts and summarize or interpret them without always relying on “he said” or “she said” or “they said.”

It’s wise to be careful with this, however. It’s important to attribute where interpretation without attribution might otherwise turn into shallow editorializing. That doesn’t just apply to reporters. It also applies to editors.

We were a team, committed to presenting the facts

The editors I worked for, almost without exception, were as committed to the facts and the truth as I was. Only rarely did I find myself defending facts and the truth they presented against an editor who wanted not so much to ignore certain facts as to push them beyond their boundaries, all in the name of “impact.”

Mostly, though, reporters and editors were a team. And we all took our journalism seriously. Respect for the facts and their inherent truth almost always kept us working together. And over the years, good editors and sharp-eyed copy desk staffers saved me many times from errors of fact.

That process was in some ways similar to but in many more ways dissimilar from the one entertainingly portrayed in the play and the book that inspired it. In real life D’Agata’s essay was finally published. In the play that is implied but not confirmed.

I like that uncertain ending, because it leaves so much to be pondered and discussed, especially in this age of many sided assaults on facts and the truths they reveal.

Now buckle up and keep a tight grip on the facts. We’re heading toward the 2024 election.